Moshe called to all the elders of Israel and said to them, “Draw forth and take for yourselves one of the flock for your families and slaughter the korban Pesach.

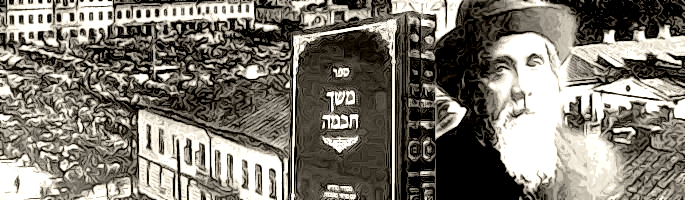

[Dedicated to the memory of Rav Yehudah Cooperman z”l, whose incisive notes to Meshech Chochmah opened up the sefer to many who otherwise would have hit insurmountable obstacles.]Meshech Chochmah: The difference between the faith of Jews and everyone else is as simple as the difference between the mind and the heart. Matters of the heart – emotions – are built upon the tangible and palpable. The heart is moved by what it experiences. We attach labels to some of those stirrings, and speak of love, and beauty, and courage. Ancient man sanctified the various forces that raged with him by deifying them. Each force became a different god. Hence, there was a god of love and a god of beauty and a god of courage. A human who excelled in one of these forces was known as a son of the equivalent god.

To this day, the world of strong emotions buttresses the belief systems of other people. The artwork and tapestries with which they adorn their holy places tap into the emotional responses of the viewers/worshippers, increasing their attachment to each particular faith.

Avraham’s way was different. He comprehended that G-d is not part of the created world in any way. He is not a force, such as we see applied to material things. He is without boundaries, limits or restraints. He cannot be comprehended or understood; if He could, He would perforce have to have some commonality with the physical world. His existence is necessary, and all existence is contingent upon Him. He brings everything into existence from absolute nothingness. His Oneness is unique, unlike anything else known to man.

All these notions are discernable intellectually, but not emotionally. Nothing that we touch or feel propels them. They exist in our rational selves. To get there, we had to elect the dictates of the mind over those of the heart. Our understanding of G-d is a product of cognition. Its depth is such that, as Rabbenu Bachya ibn Paquda[2] puts it, only the philosopher or prophet can grasp it fully. Nonetheless, all of Israel fully believes in His existence and His Oneness, despite these being entirely conceptual notions. They disparage the alternative notions that are sourced in emotion, seeing them as part of a limited, changeable physical creation, which is nothing but a tool in the Hand of its Creator.

What role did Hashem assign the palpable and emotional experiences that are part of the nature He created, so that they would not interfere with what we are to know through the intellect alone? Surely they hold great promise to us as well! We find the mission of the emotions fulfilled through Torah. He created a Torah of great complexity, which would bolster the intellectual side of man, and hence give it prominence over what his heart might suggest and his imaginative faculty might formulate.

He also apportioned the various emotions to different mitzvos. Love would be channeled into love for his fellow man, and to cement the family relationship and the commitment to peoplehood. Revenge would be focused on enemies of G-d. Loving-kindness would be directed to other people.

Every emotion that typically resides within the human heart is given its due. Beauty is appreciated on Sukkos, when we take the esrog, the “fruit of the beautiful tree.” Significantly, it is savored only for a week – after which it is discarded, unlike other mitzah material, teaching us something about appreciating the esthetic, but not overvaluing its importance.

The roles of mind and heart are memorialized in the garb of the kohen gadol. On his forehead – the seat of the intellect – he wore the tzitz, upon which was emblazoned kodesh le-Hashem/ sanctified to Hashem. Man’s rational faculties are to be kept holy, directed to his Torah study and his prayer, and free of competing influences that would lead him astray from his focus on Hashem. On the choshen/ breastplate, however, the kohen gadol carried the names of the shevatim/ tribes of Israel. Man’s heart and all the forces within it are directed to the mitzvos, the majority of which serve the unity of the nation, like the beis ha-mikdosh, and the ten portions that go to the kohen, the Levi, and the poor.

Effectively, we as a people have crowned the head to be the king over all other parts of the body! We have opted to follow the rational faculty, through which we discern the absolute Oneness of Hashem, something that cannot be directly experienced. We place our trust in our sechel; we succeed in obeying it even when that means disregarding the most deep-seated emotions. Thus, entire communities of Jews have walked to their deaths at times rather than renounce their firm belief in the nature of G-d, although this is something that cannot be felt and cannot be adequately described.

We acquired this ability at the Reed Sea, when they jumped into the sea, offering their lives, in their minds, in support of their belief in Him, refusing to reach an accommodation with the Egyptians. We can paraphrase what Chazal[3] say about Yehuda, and apply it to Klal Yisrael as a whole” “How did the Jews merit kingship? Because they jumped into the sea.” In other words, the Bnei Yisrael merited that the head, the sechel would rule over all the emotions when they jumped into the sea, indicating that they employed their sechel to comprehend the Oneness of G-d.

It is for this reason that Chazal instruct us[4] that the most impoverished man in Israel must lean at the seder in the manner of free people. Our exodus from Egypt turned out to be impermanent. We subsequently lost our freedom and our land at times. Nonetheless, every Jew on the night of the seder is indeed a free man. He has escaped the agenda of the emotions, and transcended the limits imposed by his physical nature. He has merited kingship – the coronation of the sechel over all his other parts.

Therefore our pasuk commands “draw…and take.” Draw yourselves away from the way others approach the world, yielding to the dictates of emotions and imagination. Take those emotions and employ them in the life of the family and in the love of fellow. Take a sheep “for each father’s house,”[5] which because of its size have to be shared with neighbors. The point of this is to stimulate the unity of the entire nation, not just small groups. Therefore, women participate even though ordinarily exempt from time-bound mitzvos. All of Israel can fulfil its obligation with a single offering – because joining them together is part of the goal of this first mitzvah that the nation participated in. In performing this avodah, all the feelings are channeled to the mitzvah, so that they are not free to challenge the faith of the mind, and demand visualization and concretization of G-d.

If you ask, how is it that all of Israel can rise to this lofty level? The Torah supplies the answer. “You shall shall touch the lintel and the two door-posts with some of the blood.” Those three parts of the doorway correspond, Chazal tell us,[6] to Avraham, Yitzchok and Yaakov, from whom we derive our emunah.

[1] Based on Meshech Chochmah, Shemos 12:21

[2] Chovos Halevavos, Shaar HaYichud, chap. 2

[3] Tosefta Berachos 4:16

[4] Pesachim 99B

[5] Shemos 1:3

[6] Shemos Rabbah 17:3