Avraham returned to his young men…

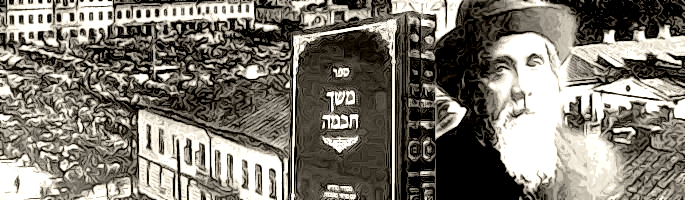

Meshech Chochmah: What do you do as an encore to the Akeidah? From the text alone, we have no clue, because Yitzchok disappears. The narrative continues with Avraham and his servants, but Yitzchok is nowhere to be found.

That’s because, Chazal tell us[2], Avraham sent him on to Shem’s yeshiva! They see the situation as analogous to a woman who became rich through her skill in spinning wool. Although wealthy, she argues to herself that her spinning-spindle was responsible for her success, and she becomes determined never to part company with it. Similarly, Avraham reasoned that he owed everything he had to Torah and mitzvos. He therefore wanted to ensure their continuity in his offspring.

This reasoning appears a bit inverted. A Jewish parent can but dream that he might educate his child to achieve a fraction of the greatness of Avraham and Yitzchok. Those two made it to the pinnacle. Why would they need Torah, if Torah’s function is simply to get people to be what they already were?

That, apparently, is the point. Chazal are trying to get us to think more precisely about what Torah is, and what it does for people.

You must know that Torah is the way – indeed, the only way – in which a Jew can fulfill himself, improving every part of his body and every level of his soul. It counters and eliminates all kinds of shortcomings that are consequences of his physical self.

But it does much more than that. Certainly it is true that Torah provides us with practical advantage in overcoming all our deficiencies. It also, however, is inherently good in and of itself. We find Hashem and apprehend Him only through Torah, which is His place of residence.

A parallel “localizning” of G-d’s immediacy applied to the mishkan. The greatest source of Divine influence flowed from the aron, which housed the luchos, the Tablets of the Law. When the aron was no longer available – as in the period of the Second Temple – the Shechinah was lacking as well. Specifically this meant that people no longer felt the Divine influence of wisdom and comprehension that they did in an earlier epoch.

This Divine influence – which exists on a different plane within Torah itself, even without a beis hamikdosh – will be important even during the messianic future, when the deficiency in Man will be sharply muted. Indeed, it remains important even after death, in the world of the spirit. Thus we find[3] depictions by Chazal of the righteous sitting in the heavenly Mesivta, debating fine points of halachah. Those souls are certainly not in need of refinement, yet they still involve themselves in Torah study.

Similarly, we are told[4] that a person should not desist from Torah study even at the time of his death. Now, if the function of Torah would be to release us from the clutches of the yetzer hora, what need would there be for Torah at the time of death? Chazal[5] prescribe a number of remedies for a person who is ensnared by the yetzer hora, with remembering his mortality being the ultimate weapon in weakening its grasp. If thinking of one’s day of death is effective, all the more so is going through the actual process. Rather, we must understand that Torah elevates a person even when it is not needed to offset deficiency or the yetzer hora.

Nonetheless, the effect of Torah practice upon one who is commanded in it is incomparably superior to the one who is not commanded, but practices of his own volition. In regard to the removal-of-deficiency effect the two are more or less comparable. (Chazal phrase this beautifully when they say that a non-Jew who immerses himself in Torah is like the kohen gadol.[6] The kohen performs the crucial avodah on Yom Kippur of purging the people of their sin – their deficiency. Similarly, the non-Jew who studies, even though not commanded, can expect to see his deficiency lessened.)

When it comes to the aspect of achieving spiritual elevation and perfection, however, the commanded and non-commanded divide sharply. The connection with the Divine comes far more powerfully to those who are commanded, relative to the non-commanded who practices or studies for the express purpose of finding some Divine illumination.

We’ve now arrived at the razor-sharp choice of words in the passage with which we began. Avraham sent Yitzchok to study Torah, in the manner of the woman who succeeded in her wool-spinning endeavor. She no longer needed the money, but could not bring herself to let go of the process that so enriched her. Similarly, Avraham and Yitzchok in the aftermath of the Akeidah did not require any removal of deficiency. They were well beyond that. On the other hand, voluntarily observing the Torah would not elevate them in the same way that it would people who were commanded to observe.

Rather than accept this rational line of reasoning, Avraham grasped the Torah, which had given him everything that was important to him. He expected neither deficiency-purging nor Divine illumination. He could not, however, let go of the beloved Torah that had already offered him so much. His thoughts after the Akeidah turned to keeping that Torah in the family another generation.

[1] Based on Meshech Chochmah, Bereishis 22:19

[2] Bereishis Rabbah 56:20

[3] Bava Metzia 86A

[4] Shabbos 83

[5] Berachos 5A

[6] Bava Kama 38A. In a similar passage regarding a mamzer who studies Torah (Horayos 13A), Chazal specify a kohen gadol who enters the Holy of Holies on Yom Kippur.