On the day that he completes his nazir-abstinence he should bring him to the opening of the Ohel Moed.

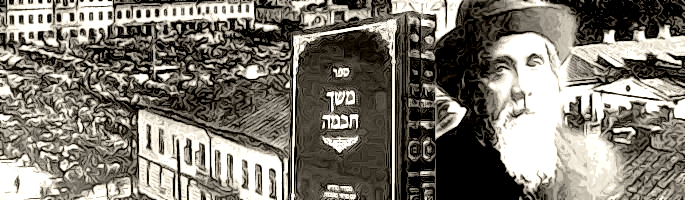

Meshech Chochmah: Who is the “he” of the second half of this pausk? Who is bringing whom? We have no indication that some third party is involved in escorting the “graduating” nazir to the beis ha-mikdosh at the conclusion of his nezirus-period!

Interestingly, we also have no clue from the text about the prescribed length of that period. Chazal teach that if the nazir himself does not specify his period of abstinence, we fix it legally as thirty days. The Torah text itself, however, does not suggest a recommended length of term.

Nor can there really be a standard term. The purpose of the institution of nezirus is hinted at in a pasuk:[2] “an abstinence of abstaining for Hashem.” Nezirus is meant to be a corrective – to help an individual who wishes to extricate himself from his lusts and pride and excess. It should be employed as Shimon ha-Tzadik celebrated it, as used by the shepherd from the south.[3] (Shimon ha-Tzadik regularly refused to take part in the eating of the offering of a nazir who had become tameh. He allowed one exception. A shepherd explained that he had knelt to draw water from a spring, and was taken in by reflection in the water. Pride welled up inside of him as he realized that he was quite good looking. To offset what he regarded as a threat to the humility he cherished, he vowed to become a nazir, and allowed his hair to grow disheveled and unattractive. Shimon ha-Tzadik eagerly hailed the shepherd’s motivation, and took part in his korban.)

No period of time can be predicted to suffice for the person warring with his inner desires. Each person needs to determine for himself how long a period will be therapeutic, and adequate to rein in his urges. He may require thirty days – or a hundred. Each person’s background and circumstances will differ from those of the next.

How can a person know when his goal of spiritual climbing has been reached? How can he determine that he has freed himself from the grip of the forces of his yetzer ho-ra that, unchecked, leave him desolate and unrestrained? When can he tell himself that his intellect exercises control over his lower desires, rather than the opposite? Our pasuk provides the answer! Our spiritual climber arrives at this destination when he is able to look at himself and his own needs as objectively as if he were looking at an unrelated third party. When he can view his situation without any worry of self-interest he can assure himself that he is enjoying the world appropriately, without engaging in excess. (Enjoy he should! Let his life-style place him firmly in the midst of the community of Man, rather than standing outside of is like an ascetic. Partaking of the physical pleasure of this world in an appropriate, i.e., not exaggerated, manner is what Hashem wants us to do.)

The abstinence of the nazir is not a spiritual summit that we are asked to climb. To the contrary. It is an artificial device, meant to be cure spiritual illness. Generally, however, abstinence is viewed more negatively that positively. The nazir is called a “sinner” for having denied himself that which HKBH permits.[4]

This is what the Torah means by “he should bring him.” The nazir’s work is done when he can stand outside of himself, as it were, and look at his needs as if he were looking at another person. During his term of nezirus, he loosened the grip of his passions and desires. That allowed him to work on his self-awareness so that he can recognize – as no other can – how much is too much, or too little – for his spiritual and physical well-being.

This necessary exercise in self-restraint and pulling back from enjoyment of the world comes with a price, which is also acknowledged in our pesukim. Every nazir [5] brings a chatas/ sin-offering as one of his offerings. In the course of his nezirus he loses the opportunity to perform some mitzvos. He cannot assist in the burial of his relatives (because he vowed not to become tameh); he must forego the wine of kiddush and havdalah (having vowed against the consumption of wine). If his nezirus-exercise accomplishes what he designed it to do, he is praiseworthy. The benefit exceeds the cost. Yet, he must address the fact that he indeed paid a price. (This is similar to the situation of a person who is disturbed by the contents of a dream, and finds it calming to fast, as he would any day of the week. He may fast even on Shabbos. But he is instructed[6] to fast another day for having fasted, thus denying himself his usual forms of oneg Shabbos!)

The chatas of the nazir deals with this. The nazir brings korbanos similar to those of the nesi’im / princes at the inauguration of the mishkan.[7] The inauguration-offerings of each nasi included three varieties: olah, chatas[8], and shelamim. The word for inauguration is chinuch, which also means “education.” Nezirus is an exercise in self-education. It attempts to teach its student how to temper an unwanted haughty spirit and diminish inflated material desires. The appropriate offering is therefore the offering of chinuch.

- Based on Meshech Chochmah, Bamidbar 6:13, 6:14 ↑

- Bamidbar 6:2 ↑

- Nedarim 9B ↑

- Taanis 11A, according to R. Elazar ha-Kappar. ↑

- I.e., not only the nazir-tameh whose days of abstinence have been to no effect since he must begin them anew ↑

- Berachos 31B ↑

- Bamidbar 7 ↑

- We can speculate that the chatas indicated not a confession of sin, but of cognizance of the power of sin, and the need to abjure it. See R. Samson Raphael Hirsch Bamidbar 7:16 and Shemos 29:36 ↑