When you come into the land that I give you, the land shall observe a Shabbos rest for Hashem. For six years you may sow your field, and for six years you may prune your vineyard…

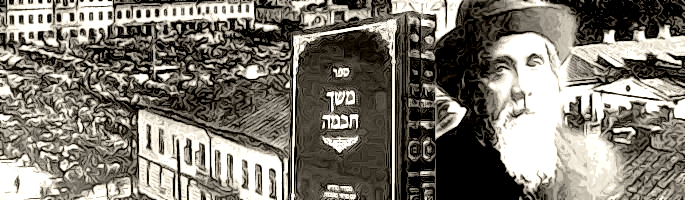

Meshech Chochmah: Two opinions in the gemara[2] face off against each other regarding the attitude of a seller. One opinion has it that sellers part with the land they relinquish with a jaundiced eye. The transaction should be assumed to be constructed narrowly; the buyer is entitled to the bare minimum of what the document or agreement explicitly states, to the exclusion of rights and privileges that conceivably could have been bundled together with the land. A dissenting opinion sees the seller transferring property with a generous spirit. Various privileges that naturally “go” with the land can be assumed to have been implicit in the agreement.

The existence of two contradictory opinions indicates to us that there is some truth to both of those positions. Both are defensible! In examining the parallel case of a gift – rather than a sale – we find no disagreement. All agree that a gift comes with the trimmings. One who bestows a gift does so from a place of generosity.

Keeping this distinction in mind, let us return to our pesukim. The first serves as an introduction “When you come into the Land that I give you…” Should you think that the laws of shmitah are meant to limit your enjoyment of the Land into which I lead you, says Hashem, think again! The land is a gift, and gifts are given generously! It could not be otherwise. A sale would require some payment, some consideration given by the buyer to the Seller. Is there anything you can give Me?

You must understand shmitah otherwise. I wish you to fully enjoy the land and its produce. The gift is predicated, however, on you living up to a standard of holiness/ kedushah, and treating the Land as holy as well. “The Land shall observe a Shabbos rest for Hashem.” The holiness of the Land is such that even if part of it is dedicated by you to Me, the laws of shmitah must be observed![3] I desire that you fill yourselves with the good of the Land. But the seventh year must testify to the place of the miraculous in My providence. Were there no other purpose for shmitah – and there certainly are! – it would be worthwhile to display the constancy of the miraculous, as the special blessing of the Land in the sixth year sustains it through the entire seventh.

Chazal[4] take note of the similarity between our “Shabbos rest for Hashem” and the Shabbos mentioned in Bereishis. This observation may have halachic importance. The styles of Shabbos and Yom Tov clash. Shabbos is set and fixed. It is just-so. Man has no say in determining to which calendar day it attaches. That decision is literally made in Heaven. Yom Tov, on the other hand, is set and determined by Man. Beis din, the Jewish court, has significant leeway in manipulating the date upon which an upcoming holiday will fall by accepting or not accepting witnesses who sighted the new moon, and in arranging ordinary and full months on the calendar. In our davening, we bless Hashem who “sanctifies Shabbos,” but who “sanctifies Yisroel and the [special] times,” meaning that He sanctifies Yisroel, who then use that holiness to sanctify the holidays.

This difference in style carries over to shmitah and yovel as well. Shmitah is a Shabbos, as shown above. Thus, if the preparatory steps leading to shmitah are not in place, shmitah will arrive on its own. Should the beis din not count off the years leading to shmitah as they are supposed to; should people fence off their property and prevent all entry – the laws of shmitah will still apply. The seventh year is a Shabbos, and Shabbos comes and goes as it pleases.

Regarding yovel/ the fifteeth year, however, the Torah instructs,[5] “You shall sanctify the fiftieth year.” The Torah treats yovel in much the same way that it treats Yom Tov. Both require sanctification by Man. Should the court fail to herald the yovel year through sounding the shofar; should servants not be freed, or land not returned to its familial owners – the other laws of yovel will simply not apply. There will be no prohibition in such a case of working the land.

Shmitah signifies Hashem’s role as Creator, and therefoe as Master and Owner of the land. Yovel, on the other hand, hinges upon awarding freedom to servants. It takes us back conceptually to winning our freedom from servitude in Egypt. Remembering the Exodus is an essential theme of each Yom Tov, a day that achieves its holiness only through the declaration of Man.