Now, write this song for yourselves and teach it to the Bnei Yisrael.[1]

Halachically, this pasuk commands each of us to write a sefer Torah. Rava[2] emphasizes that the mitzvah applies even to a person who owns his own sefer, having received it from his forebears. Apparently, the Torah wishes us to invest time and energy into the writing of a sefer Torah, apart from the pragmatic advantage of possessing a sefer to enable one’s own Torah study. Indeed, the gemara[3] salutes one who writes a Torah scroll as if he had received it at Sinai.

Elsewhere,[4] Chazal heap the same praise upon someone who teaches his son Torah. He is also like one who accepted Torah at Sinai. What is the connection?

It might be this. People observe the tenets of the Torah for one of three reasons. Some observe out of love for Hashem. Others, out of yir’ah. A third group follows the tradition of their parents, maintaining a life-style that has accompanied them since their youth. Call it force of habit, or nostalgia, or a sense of identity, they hold on to some of the practices with which they were brought up.

There are important differences between the groups. The first two are careful to teach their children the requirements of Torah living, hoping to ensure that they will be meticulous in observing laws that the parents regard as extremely valuable – whether out of ahavah, or out of yir’ah. Not so members of the third group. Were it not for “tradition,” they would have discarded the old practices themselves; they are not committed to them as practices that are legally binding. People in this third group are not so invested in seeing their progeny follow the old laws as if their lives depended upon them.

We could imagine them in an alternate history version of maamad Har Sinai. When asked whether they would accept the Torah, they would have responded, “This is not something that resonates with me!” Even now that they have had it for millennia, they treat it lightly, and have no interest in perpetuating it. It has meaning to them only insofar as it connects them with their younger days. If given the choice about accepting it in the first place, they easily would have turned down the offer.

A person who teaches Torah to his children shows himself not to be part of the third group. Torah is such an integral part of him, that he cannot see his children being without it. It is thus clear that he would have been among those at Sinai who accepted and received it there.

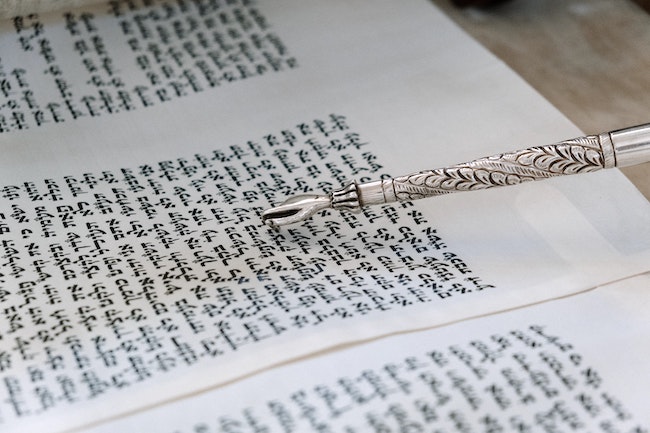

All things now fall into place. Writing a sefer Torah anew shows that a person values his own acceptance of the Torah. Indeed, he may have inherited such a sefer from the past. By writing his own, however, he shows that his observance of the Torah is not a function of family traditions, but is deeply personal and individual. Torah goes to his essence.