Yaakov arrived whole at the city of Shechem…and he encamped before the city.

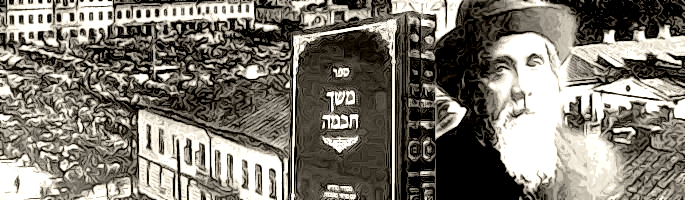

Meshech Chochmah: Chazal[2] see an allusion to Yaakov’s observance of Shabbos in the latter part of our pasuk. By encamping “before” the city, but not quite reaching its limits before twilight, Yaakov was forced to observe the laws of techum Shabbos in regard to travel within the city. While a person who encamps within a city can go anywhere within that city, well beyond 2000 amos, Yaakov could go no further than 2000 amos from the place he encamped. Since he only reached “before” the city by dark, his later entry to the city did not allow him full access to it.

This is rather unusual. It is Avraham whom we usually credit with observance of Shabbos (and other mitzvos), and then extend the assumption to the other avos who followed. The gemara[3] states that Avraham observed even the law of eruv tavshilin, i.e. he was meticulous even in the derabbanans of Shabbos. Why would there be a Scriptural allusion in our pasuk to shemiras Shabbos specifically to Yaakov, and none to Avraham? The answer may have much to do with the historical roles that the two avos embraced for themselves.

As things progress through the hierarchy of domeim, tzome’ach, chai, medaber, we see nutritional needs and preferences getting more complex. Spiritual nutrition is no different. The vast majority of human beings can subsist on a diet of the seven Noachide laws. No more is necessary. The Jewish soul – sourced in a higher place, a place within Hashem Himself – needs the Torah, in general and in all of its detail. Without it, a Jewish soul finds itself in an unsustaining environment.

Klal Yisrael is charged with serving as the host to Divinity in the lower world. This mission can be discharged only collectively, not individually. We find, therefore, that certain numbers are critical. For the Shechinah to take up residence, a minimum of twenty-two thousand are needed;[4] 600,000 varieties of soul-types present themselves to the Jewish nation.

Understanding the power of spiritual crowd-sourcing, Avraham devoted himself to widening his base. Yishmael’s decision not to follow in the path of his father increased Avraham’s concern. He reacted by creating his eshel/ hospitality center, for the purpose of bringing in the greatest number of people to the cause of Hashem’s truth.[5] Because his intention was to subordinate his followers to the Torah, Chazal speak of a two-millennia long epoch of Torah that begins with Avraham amassing those followers in Charan.[6] Even Avraham’s move to Egypt (rather than any of a number of other neighboring countries where food was available) was inspired by his mission of reaching numbers. Known for its purported wisdom, Avraham was eager to engage them in debate – and win over his audience.

Yaakov, on the other hand, came to an antipodal conclusion. Unlike Avraham, he saw children perfectly united in loyalty to his mission, and suitable to continue it. He determined that his own family could host the Divine message, without recourse to others. (This is the significance of Hashem standing over him in Yaakov’s vision of the angels on the ladder.[7] Hashem indicated that Yaakov himself sufficed to bear the Shechinah!) He therefore determined to go a very different route. He understood the need for his children to isolate themselves from others, rather than deliberately mingle with them. He circumscribed his mission, and drew limits and boundaries around his nascent proto-community. Despite living in close proximity to Lavan, he made no attempt to wean him away from his idolatry, and was displeased when Rachel stole Lavan’s terafim when she wished to help him give up his avodah zarah habit. The separation was destined to continue on in time, beginning with the exile in Egypt, where Yaakov’s family preferred to isolate themselves in their own Goshen neighborhood.

Chazal allude to all of this in speaking about Yaakov’s dealing with techumim in regard to the city mentioned in our pasuk. They mean to introduce this as an innovation of Yaakov’s that Avraham had little use for. Avraham’s meticulousness regarding eruvin is limited to eruv tavshilin – but not to techumim. The latter means drawing boundaries, borders, limits – virtual fences and barriers that prevent free association. Such boundaries were foreign to Avraham, who promoted ease of access so that multitudes could come, learn, be inspired, and change their lives because of it.

Techumim would become part of the working vocabulary of Yaakov’s descendants at Sinai – but not before. Even though the Bnei Yisrael received the mitzvah of Shabbos at Marah, weeks in advance of matan Torah, the gemara[8] teaches that eiruvei techumim was not part of the early instruction. This is consistent with our approach. On the road to Sinai, the Bnei Yisrael were still riven with dissension and dispute. They could not yet serve as a national bearer of the Shechinah and its message. Boundaries and limits to keep others out were simply inappropriate.

This changed at the Sinai encampment. In loving anticipation of the giving of the Torah, they became a single people, their hearts united in purpose and intent. They became a capable vehicle for elokus, bearing Hashem’s message through the history that would follow. Like their forefather Yaakov, they then needed techumim, boundaries and limits, to keep them separate, distinct, and apart.

This approach is crucial to our understanding of the role Hashem prescribes for us. Whereas Avraham and Yitzchok are promised the Land – an area with boundaries – the promise to Yaakov exceeds all boundaries. “You will break out to the west, the east, the north, and the south.”[9] Only because Yisrael would set up and live within boundaries do they merit unbounded blessing.

[1] Based on Meshech Chochmah, Bereishis 33:18

[2] Pesikta, 23

[3] Yoma 28B

[4] Yevamos 64A

[5] Sotah 10B

[6] Bereishis 12:5

[7] Bereishis 28:13

[8] Shabbos 87B

[9] Bereishis 28:14