When Aharon saw that all the princes brought sacrifices, except those of the tribe of Levi, his mind was weakened. Their sacrifices were accepted even though they were brought spontaneously and as a result of an outpouring of religious ecstasy, rather than of a command. He, being the essence of the mind, felt that perhaps, he and his tribe of Levi had not been forgiven for the sin of the Golden Calf, which was an error of the mind. Hashem told him his contribution was greater than that of the princes. Their contribution, together with all the other sacrifices would cease when the Temple was destroyed, whereas his lighting of the menorah would continue even after the destruction of the Bet Hamikdash and even into the Galut. This midrash (Devarim Rabba, 15) is problematic since we know that the service of the Menorah ceased together with the rest of the temple service. Nachmanides, explains that the promise of G-d referred to the lighting of the candles of Hanukkah.

There is a halakhic explanation as to why the Menorah and the sacrifices could not continue after the destruction of the Temple. The sacrifices, including the incense, were totally the service of the Cohanim alone. So too, the arranging of the Menorah, the oil and the wicks are considered to be defined as the work of the priest and forbidden to non-priests. Therefore they could not be continued without the Bet Hamikdash or in the Galut. However, the actual lighting of the Menorah was not considered to be a priestly service and so, was halakhically permitted to anyone. From this we can learn that lighting the menorah and later the candles of Hanukkah, were not restricted to the Temple as were the sacrifices and the other avodot of the Cohanim. Therefore they could be continued even in Galut.

There is, however, a spiritual connotation to the actual lights of the Menorah that distinguishes them from the sacrifices, and makes it possible to be performed even in the exile. The lights were the symbol of the religiosity and spirituality that grow from below [earthly] to the upper levels [in heaven] above. Rashi comments that the lights of the menorah were turned upward. Therefore they represent a worshipping that brings forth the human expression of ecstasy, whereby people’s eyes see upward. This is the work of the Levites through song and prayer, both of which are open and public expressions, and therefore could be continued in the Exile. The worship of the priests, however, was hidden as it was performed within the walls of the Temple and in areas where strangers could not come. The high priest on Yom Kippur went unaccompanied into the very most recesses of the Kodesh HaHedoshim, the Holy of Holies; as we read, ‘That which is performed in secret, comes to atone for the sin [of lashon harah] committed in secret’ (Yoma, 44a). Jerusalem, the site of the Temple, is surrounded by hills, another expression of the hidden nature of the Temple service. This worship is meant to bring spirituality down from heaven, to the world below and could only be performed within the confines of the Bet HaMikdash. It is true that the korbanot of the princes were the expression of their spontaneity and ecstasy, and should therefore have been possible outside of the Temple. However, they and the incense that are symbols of spirituality, were an integral part of the priestly service that limited them to the Bet HaMikdash. The lights of Hanukah, which were the service of the Hasmonean priests, were a reward for their voluntary actions and outpouring of dedication to HaShem. This continued the service of the Levites and therefore could exist even in the Galut.

These differences between the avodah of the Cohanim and that of the Levities, relate to the spiritual differences between Eretz Yisrael and all the countries of the Galut. Galut is rooted in â??gilui’ that is something uncovered and public. This makes possible the ecstatic worship from below, that urges one upward to Heaven. So there is a role for the lights even in Galut. However, just as the public domain, reshut Harabbim, halakhically can only serve to acquire ownership up to 10 tefachim, hands breadths high, so too we limit the types of worship that apply to the Golah. These countries have a â??tumah’, impurity, which seeks to attach itself to the purity of Divine worship. In contrast, Eretz Yisrael has a sanctity that does not permit evil and impurity to attach them selves to our Divine worship. It is a land that, ‘the eyes of the Lord are on, from the beginning of the year till the end of the year’. Avraham leaves his birthplace because there the Tumah of the Galut can attach itself to him. Even in Eretz Yisrael, he announces to â??Bnei Chet’, that he is a stranger and a sojourner, so that the tumah of the Canaanites should not have a connection to him and attach them selves to his worship. Therefore, the hidden worship like that of the Kohanim, that seeks to bring down blessing from on High, has no place outside the confines of Eretz Yisrael.

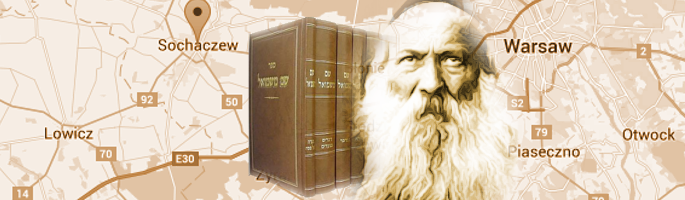

Shem Mi Shmuel, Beha’alotcha 5670, 5675.

To understand the problem of Israel’s mourning for meat, we should see the explanation of the Baal Shem Tov to Tehillim, 47:15; ‘He will guide us eternally’ He comments that when a father teaches his child to walk, he does so by continuously drawing back from the child thus encouraging the child to follow him. This withdrawal of the father is thus for the benefit of the child.

This is what Hashem did for us in the desert. There, Israel were vouchsafed a great revelation of G-d’s presence, enjoyed spiritual food [Mannah] and they were not required to do any material actions. However, that was not the purpose of Creation. The soul even before coming down to Earth lacked nothing, so the purpose of the whole Creation was that the material things of this world should, through the actions of Mankind, be used in the worship of G-d. So the Divine plan was that they should enter Eretz Yisrael, plough, sow and reap [as well as all the other material actions] needed for their existence, and would still see the service of Hashem as the end purpose.

Now that were drawing near to enter the Land [without the incident of the spies, they would enter within 3 days], Hashem began the process of gradual withdrawal, so that they would become accustomed to making the material holy. The Aron HaBrit now was no longer in their midst as they traveled as it had been till now, rather it traveled before them. Now they would have to draw closer to Hashem, through their own efforts. However, they fell slightly from their elevated spiritual position and did not trust themselves to be able to do this, so they were as complainers. They did understand that they would be helped to do this from heaven. Shem Mi Shumel,5670.

Elsewhere [5672] he explains that the food of each land has special spiritual strengths that are a reflection of the moral and religious level of that country. When they left Egypt they took with them the bread of affliction that had of the tumah and immorality of Egypt, then they ate it together with heavenly food, Mannah, until they were acclimatized to the new spiritual level. In the same way they wanted now to eat Mannah together with the earthy and material food of Eretz Yisrael, until they became accustomed to achieving kedusha through their material actions. It was only when that spiritual desire became perverted to lust for meat, vayithavu, that they sinned and Moshe was angry with them.

Text Copyright © 2004 by Rabbi Meir Tamari and Torah.org.

D r. Tamari is a renowned economist, Jewish scholar, and founder of the Center For Business Ethics (www.besr.org) in Jerusalem.