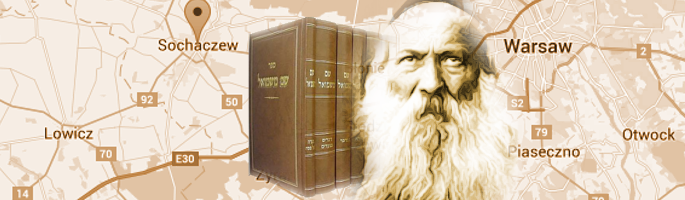

Perhaps the most definitive and special feature of Pshyscha in general, but especially of Kotsk and its offshoots, as distinct from other streams in Chassidism, is the emphasis placed on the study of the Torah Sh’Beal Peh-Talmud; Halakhah- Aggadah. In this respect, it is argued that they thereby wished to create an elitist scholarly movement. If this is in fact valid, then the primary success was in the school of Sochochow, which never became, for this reason, a mass movement, as did the other offshoots of Pshyscha for example Gur or Alexander. There are no songs special to Sochochow and few examples of miraculous deeds of its Rebbes. It was as a movement, directed to the intensive and extensive study of all the sources of the Oral Law. The term â??Oral Law’, although commonly used in many circles, is a misnomer at best; at worst it is a serious error. As such it causes much confusion and distortion, by presenting it as merely a legal system, a codex or legislation. In actual fact this is a Torah with law and spirituality intertwined, one concerned as much with morality and righteousness as it is with justice and legal decisions. As such, this study is repeatedly the basis of the Shem Mi Shmuel and this parshah affords us a view of the basic component of his commentary.

This fifth book of the Bible differs from the other four in that it is presented in the words of Moses, rather than those of G-d Himself. Since the medium is the human voice and speech, the Avnei Nezer saw it as being midway between the Written and Oral Torah; a sort of bridge as it were between the two.

‘If Israel would not have sinned, they would have been given only the five books of the Chumash and the book of Joshua because it describes the boundaries of Eretz Yisrael'(Nedarim22b). This cannot mean that there would have been no Torah Sh’beal Peh, which is the veritable essence of the Torah, since without it there would be no knowledge of how the mitzvot were to be observed or applied. Rather it needs to be understood in the light of the spiritual and religious levels of Israel at various times. At Mount Sinai, the people reached great heights of spirituality, religiosity and knowledge of HaShem. Thereby they achieved a clear insight and understanding of Torah, all its implications and even its most hidden and secret meanings. ‘Each of the Ten Commandments spoke to every individual saying,’ I represent such and such mitzvot, so many leniencies and so many stringencies. Will you accept me?'( Midrash Rabbah, Shir HaShirim, Chapter 1).

The people were able to see within the written text the complete Torah, understanding all the implications of the mitzvoth under the headings of each Commandment and their application, sensitive to the moral and ethical messages contained therein, and aware of the hidden and mystical aspects of this text. In effect they saw clearly and without difficulty in the Written Torah, the presence of the whole of the Oral Torah. However, then they sinned. First, they asked Moses to stand between them and G-d and to bring the Divine Torah to them (Shmot, 20:6), thus weakening their direct connection with Him and then they added to that the sin of the Golden Calf. Because of these sins they descended to lower levels and their spiritual and religious greatness was lost. Sin clouded their vision and the clarity of Torah was lost. The unity of Torah Bichtav and Torah Sh’beal Peh was destroyed. Since then, in order to re-establish this unity, the sages of Israel had to search to find the hints and references in the Written Torah, to the dimensions, applications and the moral and spiritual messages of the Oral Torah. They had, through the study of the written text to define and determine the methods of understanding and applying the mitzvoth, so that Israel was able once again to live with a united Oral and Written Torah.

‘Rabbi Akiva was able to erect mountains of halakhot on each letter and sign in the Torah'( Menachot 28b) creating just such an understanding and unity. Even those Sages, who did not possess the spiritual greatness of Rabbi Akiva, were able to do this through the Mishneh Torah, the book Devarim. These words of Moses, a human being, are not separated from Israel nor are they too elevated above them, so they are able to easily find in them morality, aggadah and mysticism.

Simcha Bunem one of the foundations of our school of Chassidic thought, taught that the Mishneh Torah was the most elevated of the books of the Torah and as such an important area for the study of his disciples. He instructed them to devote much time and thought to it. They would find themselves closer to it, greater relevance in its words and so the moral and ethical teachings would echo in their hearts and understanding. Being a bridge between Oral and Written Torah, it allows them to see the definitions of the mitzvot and their application, to experience the moral vision contained therein and to understand its secrets and their mystical messages.

Shem Mi Shmuel, 5670, 5675.

Text Copyright © 2004 by Rabbi Meir Tamari and Torah.org.

D r. Tamari is a renowned economist, Jewish scholar, and founder of the Center For Business Ethics (www.besr.org) in Jerusalem.