There is a school of thought, characterized by the Rambam, Rashi and others that see the weaknesses, the revolts and the sins of Israel in the desert, as the result of their slavery in Egypt. According to this school, these were the spiritual and religious effects, both of the slavery itself and of the immorality, idol worship and impurity of Egypt. They created a constant struggle within the people of Israel, that sometimes they met successfully but at others times, failed. There is another school, however, led by the Ramban [Nachmanidies], the mystic’s and the Chassidic Masters, that views the back sliding and the weaknesses, as the result of spiritual errors on the part of a generation that the sages had described as one of great knowledge and merit. After all, this generation had witnessed great miracles in Egypt and in the desert, while they had witnessed the revelation at Mount Sinai; none of these befitted a generation of slaves. It is in this tradition that the Master Samuel of Sochochow followed and his treatment of Korach, is only one example of this tradition. Simcha Bunem of Phsyscha, one of the founders of the Chassidic school to which Sochochow belonged, referred to, ‘My Zeide Korach’, and saw him as a great Rebbe.

This tradition is in keeping with the decision in the Talmud, that Korach and his congregation have a share in the World to Come (Sanhedrin, 109b). It would seem that there is a contradiction between this decision and the statement in the same source that one who denies that even a single word or a single sentence in the Torah is of Divine origin, has no such share. Korach accepted that only the Ten Commandments were spoken by G-d while the rest of the Torah came only from Moses. The reason why he, nevertheless, still had a share in the World to Come despite this claim, was because he had a great spiritual desire and an inspired religiosity; unfortunately one that he was unable to achieve.

Korach wished to correct the sins of Cain and Able, even as Moses had done. Cain is from ‘kinjan’, to acquire, to purchase or to take an action, even as Eve said at his birth, ‘I have acquired a man’ (Bereishit, 4:1). His trait was to act and to do religious acts with great diligence and effort. This is an important and positive trait, as it gives one the ability to withstand the pressures of desires, of evil or of spiritual weakness. ‘ A person should rise up like a lion in the service of God'(Orech Chaim, section 1). At the same time there is the ever- present danger of arrogance and pride in this trait, which can lead one to evil itself. His mother, therefore, had completed the phrase whereby she named him, by saying, ‘before the Lord’. Cain failed to meet the challenge of arrogance and pride. Able also had a short- coming for which he was to die. His name comes from the root of’ hevel’, vanity and he dismissed everything in this world as being a product of vanity and therefore valueless. That this dismissal applied even to Divine worship and religious acts, we see in the text, ‘And Able, he also brought a sacrifice [following the example of Cain]’. Although humility and modesty are great and desirable traits, nevertheless, they contain the root of evil. They may be lead one to despair of everything, including the ability to serve G- d and to achieve spiritual greatness. Such despair and depression is fertile soil for sin and evil. While Moses had been able to preserve the Torah balance between modesty and strength, Korach was not. Korach, by following the way of Moses in kingship could thereby correct the faults of Able. However, though he set out to emulate the modesty of Moses, still he could not shield and protect himself against the arrogance of Cain; therein lay his sin.

The Zohar tells us that, ‘Korach wanted to do away with the Shabbat and to retain only the festivals’. The Chagim are periods of â??Simcha’ defined by Simcha Bunem of Physcha as the overflowing of ecstasy and holiness. All the festivals relate to the experience of human beings, the Children of Israel, and therefore they have a partnership, as it were, with the festivals. The Bet Din even determines the calendar of the year and therefore the dates of the festivals. In the festival’s kiddush we say, ‘in joy and rejoicing’. In the kiddush of Shabbat on the other hand, we read, ‘in love and pleasantness’. Shabbat is a time of â??oneg’, that is the rejoicing of the intelligence, the mind and knowledge. Human beings have no share in the creating of the Shabbat nor does it reflect their experience; it is solely the evidence of the work of the Creator and His Mercy. It is a day that is completely devoted to Torah. Korach wanted a religion of ecstasy and spiritual experiences that did not include study, knowledge and wisdom. Judaism is a balance between the festivals and the Shabbat, between the fire of ecstasy and religious outpourings, and the cool of study and knowledge. The destruction of such a balance is an example of the faults of Korach.

When Aharon lit the Menorah for the first time the text tells us that he did exactly what HaShem told him to do. The Berditchever Rebbe explained why this was a praise of Aharon, even though we would expect even the simplest person to carry out G-d’s word. However, anyone else would, in their ecstasy and fervor, have spilt the oil, knocked over the Menorah or done other things in their spiritual outpouring. Aharon was able to suppress his yearnings and do exactly what he had been commanded to. That is his praise.

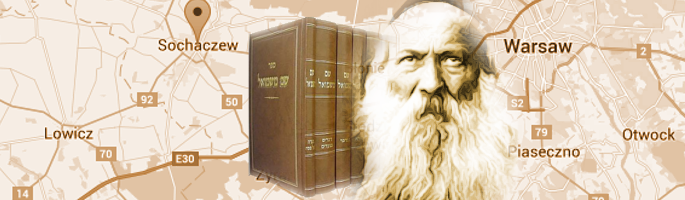

The Avnei Nezer, told his son the Shem Mi Shmuel that he once saw, the Admor of Kotsk, at prayer in privacy during Rosh HaShanah. His prayer was without motion, in silence and in perfect isolation. It was like watching a pillar of fire. This is the ecstasy of the mind that is the true ecstasy.

Shem Mi Shmuel, 5670.

Text Copyright © 2004 by Rabbi Meir Tamari and Torah.org.

D r. Tamari is a renowned economist, Jewish scholar, and founder of the Center For Business Ethics (www.besr.org) in Jerusalem.