‘On Rosh Hashanah all pass before Him like â??bnei marom’. What is the meaning of â??bnei marom’? Here in Bavel they translated â??bnei marom’ as to mean like a flock of sheep, Resh Lakish, said, it is like a steep hill, Rabbi Yehudah said that it is like the soldiers of the house of David'(Rosh Hashanah, 18a).

We can best understand their discussion by introducing the Avnei Nezer’s explanation of the Gemara there (26b) dealing with the shofar as to whether on Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur it has to be curved or whether like all the year round it could be straight…. He linked it to another discussion (Yevamot, 105b); ‘One who prays should let his eyes be downcast [at his own insignificance] and his heart uplifted [at the greatness of Hashem]’. So the one Sage who holds that on Rosh Hashanah, as on other days, it should also be straight maintains that the essence is to bear in mind the greatness of Hashem and simply adhering to Him, which is the core of straightness. The Sage who maintains that the shofar should be curved, sees human insignificance and humility as the main worship. He agrees that the greatness of Hashem and adhering to Him is the real purpose, but considers that this is not possible, so that humility is the way and therefore the shofar should be curved. This is even as the Maggid of Kuznetz explained the verse in Tehillim (138:6), Though Hashem be high, yet He has respect for the lowly, but the proud He knows from afar ‘. Hashem is exceedingly great but one who is humble in his own eyes can see this; however, one who is proud and considers him-self important is unable to see His glory and greatness.

Now we can better understand the different interpretations of â??bnei marom’ and their meaning for our worship on Rosh Hashanah.

The opinion in Bavel that it means a flock of sheep, teaches submission and negation of self, just like sheep proceed head to tail of each other without being separate. There is inherent in this a feeling that, ‘I have strayed like a lost sheep; seek Your servant, for I have not forgotten Your commandments’ (Tehillim, 119:176). In such a mind frame, one sees one- self as a lost sheep and then there is a danger that one can be brought to great despair and a serious loss of any hope, that is worse than anything else.

One should consider it as though one is ascending the slopes of bet marom. Rashi explains the steep hill of Resh Lakish as having precipices on either side. Because there, those ascending have a fear and there is danger in looking aside, so one needs confidence that one is able to scale the heights. Each should see only the person in front and look neither to the left nor to the right and thus become aware of the precipices. Then there is hope that one will be successful in ascending.

The interpretation of Rabbi Yehudah that bet marom, is like the soldiers of the house of David, teaches that there is still the fear of despair and hopelessness. So one should be confident and determined as were the soldiers of David. ‘ Everyone of the soldiers of David who went out to battle, wrote a bill of divorce from his wife’ (Ketubot, 9b). The Admor Menachem Mendel of Kotsk, explained that they did so in order that they should no distracting thoughts of their homes or families. All their thoughts and strengths could then be devoted to the forthcoming battle. In this way they could definitely be strengthened to gain victory in the Name of Hashem and the tzelem elokim that is upon their faces. So should each of us be in his own eyes, and have confidence in Hashem. The greater our cleaving to Him is, and the more we engross ourselves in the thoughts of the Torah, the greater will be our victory.

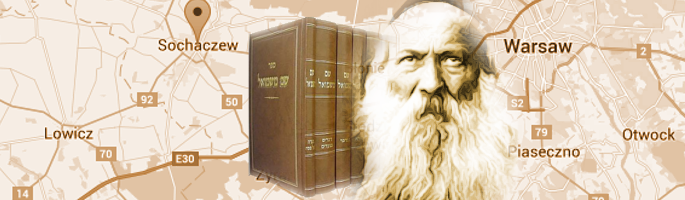

Shem Mi Shmuel, Zechor Brit, 5672.

The whole discussion has an additional perspective if we consider the Gemarah in Yevamot in conjuction with the continuation of that Gemarah in Rosh Hashanah. ‘One Sage says, the more a person humbles himself and his mind as he bends in prayer the better it is. The other Sage says, the more a person elevates himself and frees his mind from crooked and irrelevant thoughts, the better it is ‘(Rosh Hashanah, 26b).

In another place the Shem Mi Shmuel, explains that during the whole year both a shofar that is curved and one that is straight may be used, since there is a necessity both for humility and for raising oneself in Hashem. However, on Rosh Hashanah there is only place for humility and surrender, because that is the Avodah of this day.

DEAR READER,

As we are completing our class in the Shem Mi Shmuel, I would like to draw your attention to my new class in Torah study of parshat hashavuah according to Don Yitzchak Abarbanel, that will be available on this web site as from Shabbat Bereishit.

DON YITZCHAK ABARBANEL,

A TORAH SCHOLAR FOR OUR OPEN SOCIETY.

INTRODUCTION.

This Torah scholar, diplomat, financier, mystic and leader of his people, although living some 5 centuries ago, is particularly pertinent to the modern open society and global village in which we live, in a way that no other scholar seems to be. He is probably the last person to combine within his person 4 major and long existent Jewish traditions; philosopher, statesman, torah scholarship and cabbalist. His commentary on the Torah seems particularly suitable to those of us who earn our livelihoods, engage in business or professions and willy-nilly are confronted with the challenges of living globally, for the first time since his period, in free societies.

Faced with the challenges inherent in the cultural and religious free market of his time – 15th century Spain, his knowledge of Torah, philosophy, both Jewish and that of classical Greece and European Renaissance, and mystical sources, he presents a commentary suitable to us living in a similar assimilatory prone, open and spiritually free society. As a scion of traumatic Jewish expulsion, persecution and suffering, his ideas of galut, redemption and messianism are extremely relevant to our post holocaust generation.

Adopting a special Socratic style of detailed questions and answers, he produces a commentary on the Chumash and the Nach that is familiar and convenient for us trained as we are, knowingly or unknowingly, in Greek methods of thought and those of science and technology. Furthermore, he constantly refers to the classical commentators who preceded him- Rashi, Rambam, Ibn Ezrah, Ralbag and Ramban. However, like a breathe of intellectual fresh air, he does not hesitate to question and dismiss their comments and supply his own.

Text Copyright © 2004 by Rabbi Meir Tamari and Torah.org.

D r. Tamari is a renowned economist, Jewish scholar, and founder of the Center For Business Ethics (www.besr.org) in Jerusalem.