Raining on the Parade That Wasn’t1

You shall not make the land in which you are a hypocrite. Blood makes the land a hypocrite. For the land there is no atonement for the blood that is spilled other than the blood of him who spilled it. Do not make the land in which you live, in the midst of which I am present, tameh, for I am Hashem who is present in the midst of Bnei Yisrael[2]

In other times, and for other people, the home-coming preparation would have focused on a gala parade. The Torah, however, chooses to speak about death. Far from being morbid, however, the Torah’s instructions for entering Eretz Yisrael are exhilaratingly life-affirming.

The Torah uses an unusual expression. “Do not turn the Land into a hypocrite.” How can land be guilty of hypocrisy?

We call someone a hypocrite when he seems to be something different from what he really is. In other words, we detect that his inner self, his essence, does not match what we see in his external behavior. What he externalizes may seem righteous and pure, but we learn that he is not like that at all at his core. You might say that when we judge someone to be a hypocrite, we preserve his external actions, but strip away the inner self that he had assumed to be what animated those actions. The actions remain detached from what ought to be inside.

The Hebrew nicely supports this. The root of the verb that the pasuk uses is חנף. We see it as related to ענף the branch that supports the fruit that springs from it. The substitution of a ches for the ayin is an expression of negation. What appears to be a branch does not fulfill its design and its promise. It does not bear the fruit that is expected of it. It looks like a proper branch, but looks are deceiving – as in the behavior of the hypocrite.

A land can be made into a hypocrite if it, too, has an inner core besides an outer manifestation. Eretz Yisrael is such a land. When the sun shines, when the rains fall, when the soil yields its bounty, Eretz Yisrael seems to respond to its productive purpose. But there is no blessing in it, unless it nurtures the most important produce of the Land. Not every failing turns the Land into a hypocrite, just as not every human imperfection justifies calling its owner a hypocrite. The failing has to be deep, shocking, and profound.

In the pesukim above, the Torah identifies that failing. Many centuries earlier, the progenitor of those ready to enter Eretz Yisrael stood at a different threshold. About to leave the security of the Ark, Hashem announced that He would not watch the spilling of Man’s blood without consequence. Whoever spills blood would forfeit his own[3]. Before Noah stepped out on to a new earth to begin a new civilization, Hashem established the sanctity of human life, formed in G-d’s image, as the non-negotiable premise of earthly existence. It was to be the sine qua non of life on earth as a whole.

Now, with Bnei Yisrael ready to take possession of its special place on that earth, Hashem reiterates the same standard: Safeguarding the life of man created in G-d’s Image would have to be the paramount concern. Human life is the most precious liquor that flows in the Land. When it is spilled, when the purpose of the Land is thus compromised, the Land becomes a soulless shell. Spilling innocent blood shows carelessness towards the value of life, and therefore a rejection of the highest purpose of the Land. When the murderer walks freely, mocking the life that he snuffed out, the dignity of life suffers even greater offense. The externals are there, but they are no longer related to the inner core from which they should spring. Atonement comes only by shedding the blood of the murderer, by someone championing the value of the victim’s blood sufficiently to declare to all that a murderer forfeits his right to remaining among the living.

So far, the Torah establishes the sanctity of life as the basis of existence within the Land. The Torah then turns to more subtle concepts that apply to life within the Land. Both ישיבה, or the national dwelling together in a Torah society, and שכינה, making a home for the Divine Presence, are also predicated upon properly valuing human life. Could it possibly be otherwise? Chazal’s teaching emphasizes three crucial values important for a Torah society: justice, love for others, and personal kedushah. Attaching enormous importance to human life figures prominently in the development of each of these.

Can there be justice without recognizing the value and holiness of the other? Love and kedushah require that a person recognize the sanctity of his own life. Many people devalue the importance of their own existence. Remove the Divine spark from it, and what is left is animal existence. Where that animal existence fits on a continuum – seeing the human animal as “higher” or “lower” – is relatively unimportant in achieving consistent morality. Man’s core without reference to the Divine will ineluctably be reduced to what he shares with all other animals: self-interest and the instinctual pursuit of interests compelled by his physical nature.

Tumah, essentially, is being in the thrall of that physical compulsion. It comes from seeing ourselves limited by our physical nature. It is the polar opposite of taharah, which liberates Man’s spirit, and allows him to function freely as a moral agent, acting by choice, and not through what his biology or his environment force upon him. Trifling with the sanctity of life can only come through being mired in the physical, and disregarding in part the place of the free will that transcends it. This indeed makes the Land tameh, as depicted by the pasuk.

Even unintentional homicide has to be viewed as an affront to the Land’s purpose. If human life is sacred, no person should ever lose sight of its importance long enough for accidental – but preventable – deaths to occur. Manslaughter may by unintentional, but it is always foreseeable to people who are morally focused.

Our pesukim are a coda to the Torah’s instruction regarding the cities of refuge for the unintentional killer. The Torah emphasizes through this that none of the other lofty goals of a Torah society in our holy Land are possible without putting the value of human life on a pedestal. The unintentional killer must flee to one of the special cities, and remain there until the death of the Kohen Gadol.

Here, too, the Torah intertwines the entry into the Land with the beginnings of human civilization. Kayin was the first murderer, and (never having known what murder was about) was dealt with less severely than those who followed him. He was not struck down by Hashem’s court, but exiled. He was not asked to pay the price of giving up life itself, but he had to give up so many of its usual privileges. He would never sink roots in a place of his own, never know the pleasure of finding a place that would be truly his.

Every unintentional killer who flees to a city of refuge experiences something similar. His plans, his place in society are aborted and changed. For ending a life, albeit without malice and forethought, he is not denied life, but denied much of its quality. We should see this not as punishment, but, as the gemara has it – as proper expiation of his sin[4]. He remains there until the death of the Kohen Gadol. The gemara[5] finds several ways to link the murderer to the Kohen Gadol. Had his tefilah been sufficiently potent and effective, no accidental homicide could have occurred on his watch. Even a Kohen Gadol appointed after the deed (but before the verdict) could have staved off a sentence of galus improperly pronounced.

It is likely that the gemara does not mean that every Kohen Gadol must be seen as a partner in each and every death. It is quite possible that the gemara offers these lines of reasoning simply as illustrations of the connection between the role of the Kohen Gadol and the incidence of accidental homicide. The Sifrei[6] distills the essence of the relationship – really the tension – between the two. “R. Meir said: A killer shortens the days of Man; the Kohen Gadol lengthens them. It is not proper that the one who shortens should dwell in the presence of the one who lengthens. Rebbi said: A killer makes the Land tameh and removes the Shechinah; the Kohen Gadol causes the Shechinah to rest in the Land. It is not proper that the one who makes the Land tameh and removes the Shechinah should dwell in the presence of the one who causes the Shechinah to rest in the Land.” In other words, the mission and theme of the Kohen Gadol are incompatible with carelessness about human life. One who is guilty of the latter must be banished from the presence of the Kohen Gadol as long as that Kohen lives.

The Kohen’s job assignment includes two main components: kaparah inside the beis hamikdosh, and teaching outside of it. The lion’s share of his kaparah- avodah deals with unintentional sin, with shogeg. The Kohen brings home to each would-be penitent that unintended actions have moral weight. Were people more vigilant and more serious about their actions, the unintended would not come to pass. The death of a victim through someone’s lack of precaution flies in the face of the kaparah-message of the Kohen.

The Kohen delivers that message when the deed has already been done, and the owner of the korban stands before him. The other role of the Kohen aims at reducing the number of people who will require his kaparah-assistance. By serving as a teacher among the people, the Kohen hopes to develop within them the proper seriousness and focus in life that precludes the careless slip-up, as well as a fuller appreciation of Man’s moral freedom, which is the antithesis of tumah.

The loss of life through unintentional killing is a repudiation of both of these roles. The killer is banished from the presence of the Kohen Gadol, whose office is the very symbol of those values. Most fittingly, the killer’s rehabilitation takes place quietly and without fanfare in the cities of refuge, which are also cities of the Leviim, the anonymous and unsung assistants in the roles of the Kohen.

Taken together, then, the Torah’s treatment of manslaughter and the two verses of summation that follow it should not be seen as a puzzling focus on a single detail of life in the Land of Israel. Rather, they amount to a glimpse of the Constitution of a Torah nation, with reverence for human life elevated to the first item in its Bill of Responsibilities, rather than rights.

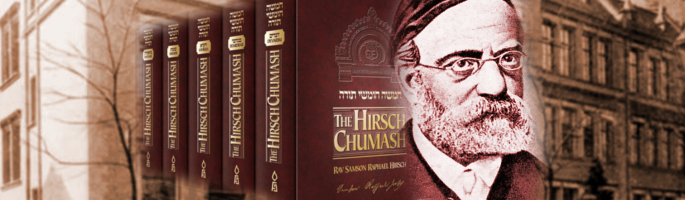

1. Based on the Hirsch Chumash, Bamidbar 35:33-34

2. Bamidbar 35:33-34

3. Bereishis 9:6

4. See Makos 11B and Tosafos s.v. midei galus

5. Makos 11B

6. Bamidbar 160