You [Moshe] shall command the Bnei Yisrael that they shall take for you pure, pressed oil for illumination…

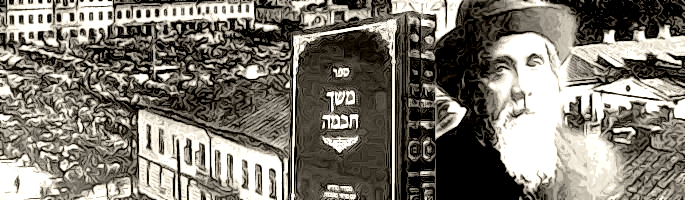

Meshech Chochmah: We read last week about the chief kelim of the mishkan. They included a menorah and a shulchan. The mishkan served as a model for other central places of avodah, including both batei mikdash. Thus, both of them also contained a shulchan and a menorah.

At least the second one did. Shlomo’s, however, had multiple menorahs and multiple shulchanos. This begs for an explanation. If increasing the number was such a good idea, why did we revert to the single menorah model for the second bais hamikdosh?

An answer may begin with our pasuk. Why do the people take the oil specifically for Moshe, as implied by the words “for you?” The mitzvah was not given only to him. Why is its purpose or benefit linked to him? We might find an answer in the position of the Ibn Ezra regarding the times at which HKBH spoke to Moshe.

We are aware of the limitation that Chazal put on Hashem’s availability to Moshe. This experience, they say, was a daytime phenomenon. Hashem did not speak to Moseh at night. The ibn Ezra, however, does not see this as linked to the time of day so much as to the presence of light. When the night is well-illuminated through lamps, Hashem would speak to Moshe as surely as He did during ordinary daylight hours. For Moshe, then, the light of the menorah had great meaning and purpose, which was not shared by anyone else. Man’s mind is clearer when he is surrounded by light, which puts him in a better, more joyous mood. Simchah is a precondition to any kind of prophecy. Thus, the menorah’s light enabled him to engage in direct conversation with HKBH during the times when natural light was unavailable.

After the death of Moshe, the menorah’s light served no direct purpose as a provider of physical illumination – not to Hashem, and not to anyone else. Rather, Chazal[2] tell us that it offered testimony to the rest of the world that the Divine Presence was comfortable resting with the Jewish people. When G-d cherished them, the ner maaravi burned the entire day, after the other lamps had already gone out. This was a powerful statement by Hashem that He resided, as it were, with His people.

Assuming that after the death of Moshe the menorah’s function became entirely bound up with representing the kavod of the Shechinah, we can understand Shlomo’s decision – at least according to the opinion[3] that both the extra menoros and shulchanos were fully functional.[4] The mishkan’s dimensions were 10x30x10 amos, for a total of 3000 cubic amos. Shlomo’s heichal, however, was 20x60x30, or 36000 cubic amos, twelve times the volume of the mishkan. If one menorah sufficed for the much smaller structure, twelve would be needed to represent the kavod of the much greater space filled by the Divine Presence!

In fact, Shlomo did not bring the number to twelve. He added ten of his own, to yield a total of only eleven. He did this to retain symmetry. The ten he added formed two groups of five; each group was placed to one side or another of Moshe’s menorah. Had Shlomo insisted on full proportionality, he would have been forced to place five on one side and six on the other, leaving the arrangement unbalanced.

In the avodah of the shulchan, we find that the Torah insists that it be “opposite” the menorah. From this Shlomo understood the link between menorah and shulchan. It followed that each additional menorah that Shlomo provided had to be associated with an additional shulchan.

All of this thinking was mooted by the destruction of Shlomo’s beis hamikdosh. The second bayis would not know of the open display of Divine Presence of the first. There would be no need for extra menoros or extra shulchanos. The configuration reverted to the essential design dictated by the original mishkan.

[1] Based on Meshech Chochmah, Shemos 27:20

[2] Shabbos 22B

[3] Menachos 99A

[4] Other opinions have it that the extra kelim were set in place, but not used, or that all were used, but only one at a time.