Remember that you were a slave in the land of Egypt, and Hashem took you out…Therefore Hashem your G-d commanded you to observe the Shabbos day.

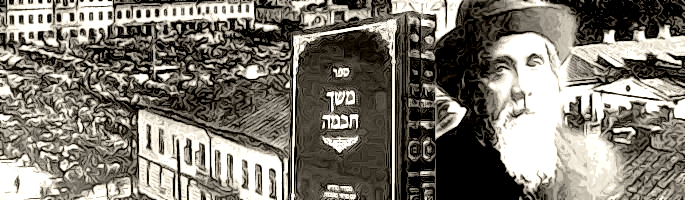

Meshech Chochmah: There is no gainsaying the fact that the most important basis of Shabbos is G-d’s creation of the world in six days. Without seeing Hashem as the deliberate Creator of all everything in the universe, we lack the logical underpinnings for important principles like Divine providence, and reward and punishment. We are not surprised that Chazal considered transgression of the Shabbos laws to be the equivalent of the rejection of the entire Torah.

So fundamental is Shabbos to our relationship with G-d, that we would inescapably conclude that all human beings ought to observe it! Are not all people expected to know Hashem and submit to His authority? Yet not only is Shabbos not mandatory for non-Jews, we consider such observance for a non-Jew to be a major offense! Why have we snatched away Shabbos from the public domain and made it a Jewish exclusive?

The answer is simple. Understanding that G-d is the Creator is a fundamental part of any person’s belief in Him. But who can testify to its veracity? Is there any group, other than the Jewish people, who are positioned to do so? Who else, in large numbers, witnessed G-d toying with the laws of Nature, as He did in Egypt – and as only the Creator of those laws could do? Who miraculously passed through a parted Reed Sea? Who was led, night and day, by pillars of fire and cloud, manifestations of His presence? Who was nourished for decades in a wildnerness that could not sustain life on a large scale? Could any other people replace us in the words of the prophet, “You are my witnesses, and I am G-d?”[2]

Our pasuk is thoroughly understandable. “Therefore Hashem…commanded you to observe the Shabbos. You – to the exclusion of others. You – because you attest to its truth, even though thematically, that truth applies to all inhabitants of the planet. Because Shabbos could, in principle, have been shared by all, Chazal[3] call Shabbos a “wonderful gift.” It is seen as a gift to Klal Yisrael, because others could have received it as well.

The case for Jewish monopoly on the biblical holidays is more straightforward. Each one deals with an exclusively Jewish event. The reason for Shabbos as a day affirming G-d as Creator would apply had there never been a Jewish people who left Egypt, stood at Sinai to receive the Torah, dwelt in the protection of the Clouds of Glory, sinned and achieved atonement. The holidays are there only because of the Jewish experience. They are sanctified not innately, as is Shabbos, but by the Jewish people. Hashem sanctifies them; they in turn sanctify the holiday. Because the holiday’s sanctity is derivative from theirs, it follows that they are a greater source of kedushah than the holiday! Food-related activities are therefore permissible on Yom Tov – unlike Shabbos. Yom Tov’s holiness is less than that of the people, whose needs therefore trump it.

The difference between Jewish and non-Jewish appreciation of Shabbos and Yom Tov finds its way into halachah. Tosafos[4] wonder why it is forbidden to ask non-Jews to bury a deceased Jew on Shabbos, given that we are allowed to ask non-Jews to perform melachah for us for a mitzvah purpose. They answer that it is odious and disgraceful to the deceased to be buried thusly on Shabbos. Tosafos do not mention that there is no parallel odium involved in burying on Yom Tov through non-Jews![5] Why should a Yom Tov burial be any less disgraceful?

According to our observation above, the difference is clear. Non-Jews have no role whatsoever in the holidays – but they can and do relate to the message of Shabbos. Because they can understand Shabbos’ message, they will be contemptuous of our apparent ignoring of its holiness by arranging a Shabbos burial. The holiday violation simply doesn’t register with them.

A passage in Chazal[6] strikes us as incomprehensible. It speaks of a king who had but one daughter. He loved her very much, and called her “my daughter.” In time, his love grew and he called her “my sister;” as his love continued to grow, he called her “my mother.”

We can understand it well if we first explore the difference between several familial relationships. The maternal relationship with a newborn is largely one-sided. The mother brings the child to life, and continues nurturing it. The baby is incapable of directly reciprocating. Siblings, on the other hand, can operate on a level playing field, each giving to the other in equal measures.

The passage deals with the three regalim. The king is Hashem. At Pesach, He did all the giving, like a mother to a daughter. The Jews at the time were not, according to the angels, very different from the Egyptians. Both worshipped idols.[7] Even the few mitzvos they were able to perform were engineered for them for the purpose of providing them with essential merit. Left to themselves, they had little to offer in the relationship.

That changed with the passage of time, and the giving of the Torah. Here, the relationship was more level. Hashem gave the Torah, to be sure. But they provided value by being the only ones willing to accept the Torah. The relationship was reciprocal.

By Sukkos, it was the Bnei Yisrael who poured material into the relationship, while Hashem was relatively passive. They spent a summer repenting for the sin of the Golden Calf. They reacted with alacrity to the mitzvah of building a mishkan, and threw themselves into its construction. It was as if, kivayachol, the Bnei Yisrael took on the role of “mother” to the King, becoming the givers in a one-sided relationship.

The midrash adds a few words each time it talks about the changed names that the king assigned to his daughter. “He did not move” until he called her sister, mother. Even though Klal Yisrael matured, and was able to bring something of its own to the table, so to speak, the essential relationship did not change. Even when the King could label the daughter a sister or mother, “He did not move” from the original relationship, which is the most essential. We cannot really give Him anything.

He remains like the mother, giving, but not receiving, anything from mortal Man.