‘ Take the sum total of the whole congregation of Israel…every male by their head count’ (Bamidbar, 1:2).

The Hebrew refers to ‘golgulotam’ literally their skulls and to ‘si’ooh’ literally to behead as we see in the case of Pharaoh’s chief baker or aggrandize as in the case of his cupbearer. So that the counting was to be done only in reference to their minds sited in their skulls and not to include the body and nefesh; Onkelus translates â??rosh’ as thought. Now we read at Matan Torah, ‘And if you hearken well unto Me and observe My covenant’ (Shmot 19:5), the listening refers to the study and the learning while the observing refers to the carrying out of the actions commanded. In every mitzvah there is a revealed and obvious element, the actions connected to that mitzvah. Then there is also a hidden element that is the wisdom and the emotion underlying the mitzvah. Of itself the action is like a body without a soul, whereas of themselves emotion and wisdom are like a soul without a body, unborn, ineffective and unrealistic. By combining both action [this world] and the wisdom and emotion [world to come] one merits both worlds.

‘He [Rabbi Elazar ben Azariah] used to say: One whose wisdom exceeds his deeds is like a tree whose branches are many but whose roots are few [and weak]. The wind comes and uproots it and overturns it upon its top. But one whose deeds are greater than his wisdom is like a tree whose roots are many [and deep] but whose branches are few. Even if all the winds of the world come and blow upon it, they cannot even move it from its place. ‘ (Avot, chapter 3, mishnah 22).

Now we learn in many of our sefarim that the importance and value of heavenly matters are in relation to material and mundane things as are roots to branches. Accordingly, one whose actions are all only for the sake of heaven is compared to a tree with many roots, so that not all the winds [evil thoughts and strange ideas] cannot entrap him in their net nor move him from his purpose. A person, however, whose wisdom is greater than his deeds, that is, they are not done solely for the sake of heaven but there are other considerations, has turned secondary values into primary values and vice versa. So the Tanna of the mishnah compares him to a tree with many branches but few roots. Furthermore, we should note that in both cases the reference is to the blowing of the wind; that is to say that in the absence of any wind [strange and evil thoughts] both are in no danger. It is only the presence of these winds that the one can be turned topsy- turvy while he whose deeds are many [for the sake of heaven] cannot be moved.

It should be remembered that the mishnah is not talking about people who have rejected Torah and Mitzvot. Judaism does not refer to dead people or to actions, few or many, that are evil, in which case they have nothing; as the Ramban points out, they are simply accursed and will not have any existence. On the contrary the mishnah is discussing those who observe all of the mitzvoth, but consider the perfection of their souls the paramount purpose of that observance. So that they are doing no wrong, however, they are affected by any wind that blows and any strange and incorrect thoughts that may come their way; therefore, harmful forces can confuse his thoughts and deeds till they become his accusers instead of merits. Whereas, when all ones actions are done only for the sake of heaven, then external and strange thoughts are not allowed to criticise. The Maggid of Mezeritch, the Baal Shem Tov’s successor taught that even in prayer, one should not that G-d should remove his troubles or pains but rather one should pray for the anguish of the Shechinah.

So it behooves every person to see that all ones actions should only be to serve heaven, and then no wind of evil and strange thoughts can move us; our actions resemble the deepest roots. However, if these same actions, Torah and Mitzvot have any other reason such as the perfection of the s9oul, then they are not for the sake of heaven, rather for our own sakes. Then, as long as there is no wind, there is no danger. However, the slightest wind of strange and unsuitable thoughts can turn us spiritually upside down. There is, even in such cases, still hope. Perhaps, in the course of time, many strong and deep roots will grow; ‘Actions done not for the sake [of heaven], we can come to doing them lishmah’ (Pesachim, 52). [ In contrast, the Admor of Kotsk is quoted, ‘ What is not done lishmah, remains â??lo’lishmah’].

When Israel lost the great level of holiness that they had had at Matan Torah, their actions no longer were for the sake of heaven. Now that they acted for reasons and purposes of their own souls and not solely for Hashem, they substituted marginality for the crucial and intrinsic. So false and strange winds could confuse and mislead them, till they saw only darkness and turmoil that led them to errors, and caused them to make the Golden Calf. Then there remained of na’aseh ve nishmah only nishmah as they had no intention of accepting idolatry or had changed their concepts, rather there were only mistaken actions. Since with nishmah only it is impossible to exist, that hearing brought them back to include na’aseh; â??lo lismah’ brought them â??lishmah’.

Now we understand the midrash (Devarim 1) which taught that if thei wisdom Âskulls- merant that their actions were only for the sake of heaven then â??saheu et rosh’ meant to raise them up, but if not then it meant decapitation.

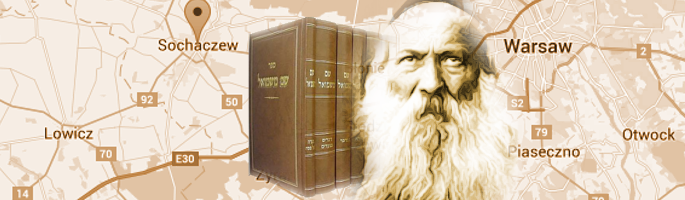

Shem Mi Shmuel, Bamibar, 5673

Text Copyright © 2004 by Rabbi Meir Tamari and Torah.org.

D r. Tamari is a renowned economist, Jewish scholar, and founder of the Center For Business Ethics (www.besr.org) in Jerusalem.