‘This will be the reward when you listen to the social laws [mishpatim] and you observe and perform them; Hashem, your G-d will safeguard for you the covenant and kindness that He swore to your forefathers'(Devarim, 7: 12).

It is difficult to understand why the mishpatim should be the observance that brings with it this reward, when there are in the Torah also Chukim and Eiduyot [witnesses to the Covenant between Israel and HaShem, the Chagim etc.]

Our text mentions three different activities with regard to the social laws, listening, observing and performing, corresponding to the brain, the heart-nefesh and the body. When one listens to something this is transmitted to the brain and becomes part of our wisdom. Performing is something that is done by the body. Observing [shmirah] means to take it to heart, to fervently desire the fulfillment thereof or to look forward to an occurrence; ‘and his father [Ya’akov shamar] observed the matter’, Rashi explains, waiting and anticipating.

It is difficult to understand how this avodah of the heart and the fervent desires, apply to these social laws. After all, such laws only come about as a result of claims for damages, or because of a non- fulfillment of obligations, or the need to transfer money and property from one person to another. It seems that normally it would be better if we would have neither the causes of such laws nor the laws themselves. However, the application of these laws does not only have an effect here on earth and in regard to material matters. All judgments in such laws have an affect also in the Heavens above and G-d’s treatment of human beings. For example judgments regarding monetary matters awake in the heavens above, the justice that prevents evil thoughts and desires from growing close to something that does not belong to them; the definition of theft being anything that comes into our possession but does not belong to us. When all of Israel’s actions are for the sake of Heaven and they desire and yearn for these Mishpatim for His sake and not for their own welfare or interests, even matters of this world acquire holiness. This demonstrates their devotion to G-d more than the observance of the Chukim or Eiduyot, since thereby they subject their own affairs to Him.

The Mishpatim require more wisdom than the Chukim and Eiduyot. In the latter two cases, it is relatively easy to distinguish between that which is permissible and that which is forbidden, between kasher and non-kasher or between pure and impure, since there are obvious and clearly defined definitions. However, to judge between conflicting claims of two parties, both of whom earned their money in holiness- morally and legally- requires great wisdom if one is to decide what the real holiness dictates. Wisdom- chochmah- that is emotive, filled with astonishment and passionate is something distinct from knowledge-da’at. The Chidushei Harim, the first Admor of Gur, questioned why we did not recite the brachah for da’at, the first one of the berachot of the weekday brachot, even on Shabbat, since knowledge seems to be spiritual, unlike the other requests in the Amidah, that are for material things. This is because da’at is not something intrinsic of itself, rather the Midot react dispassionately to the mind- seichel; like a scholar who foretells the future of a distant kingdom with complete personal detachment. Nevertheless, da’at is an essential part of human beings, distinguishing them from the animals, which is why we use â?? beseech’- the language of a gratuitous gift- in this beracha. Since it is actually not a spiritual factor we do not pray for it on Shabbat.

If the text would mention the Merits of the Fathers, zechut avot, as being the entitlement of Israel to Eretz Yisrael, the sons of Eisav would be able to claim their part of the Abrahamic inheritance, since we learn that an apostate has a share in the property of his father (Kiddushin, 18a). It is the great desire and yearning for the mishpatim, the shemirah- observance, that brings with it the blessings of this world and therefore retains the Abrahamic covenant only for Israel.

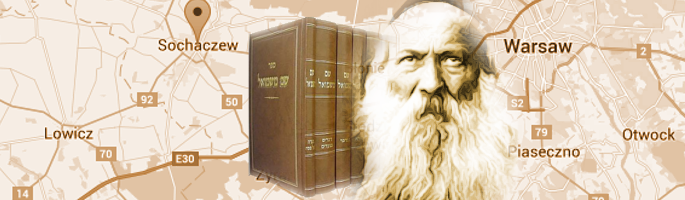

Shem Mi Shmuel, 5673.; 5676.

Commentating on the verse, ‘He perceived no abuse of power [aven] in Jacob and did not see worry [amal] in Israel'(Bamidbar, 23,21), the Admor relates it to this same theme. â?? Ya’akov-Jacob’ refers to the nation in its lowest spiritual stages, one who clutches the heel of Eisav or is an exiled or persecuted person. In these conditions their material affairs and social behavior, are devoted to satisfying the needs of a human society, without dishonesty, fraud, and any exploitation of power. When they are at the highest level, Israel, they are able to go beyond this. Here, they devote their human activities to serving Him, using their money for charity and their time for Torah.

Perhaps, the Shem Mi Shmuel’s approach here follows that of the Admor Menachem Mendel of Kotsk, when he explains the opening verse of Mishpatim, ‘ These are the Mishpatim that you shall place before them’ (Shmot, 17:1). The Talmud explains, ‘before them and not before the nations of the world’ (Gittin, 88b). How is this possible since we know that all civilized nations have social laws and economic ordinances? ‘Yes’, said the Admor of Kotsk, ‘but only by us are these mishpatim an Avodah, a service of HaShem’.

Text Copyright © 2004 by Rabbi Meir Tamari and Torah.org.

D r. Tamari is a renowned economist, Jewish scholar, and founder of the Center For Business Ethics (www.besr.org) in Jerusalem.