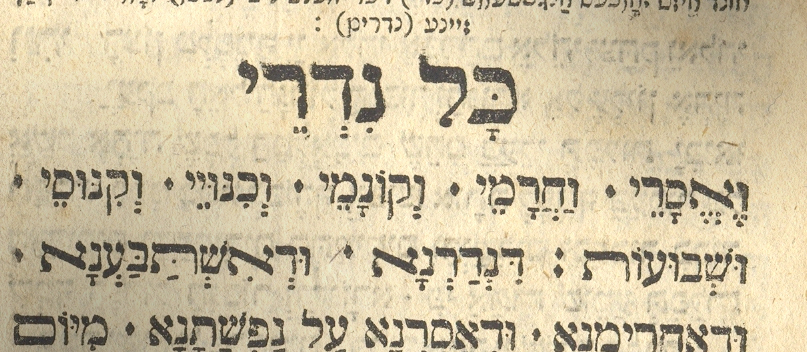

The holiest day of the year, the day which the Torah designates as a Day of Atonement for the sins of the Jewish people, begins with the little understood but emotionally charged Kol Nidrei service. For reasons which are not completely known to us, the compilers of the Yom Kippur machzor chose Kol Nidrei, which is basically a halachic procedure for annulling certain oaths and vows, as the opening chapter of the Yom Kippur services. Obviously, then, there is more to Kol Nidrei than meets the eye. Let us take a deeper look.

It is known that Kol Nidrei dates back to ancient times, possibly as far back as the era of Anshei Keneses ha-Gedolah[1]. The earliest written version, though, is in the Siddur of Rav Amram Gaon, who lived in the ninth century. Already then, the exact reason for reciting Kol Nidrei on Yom Kippur was not clearly understood, and the Geonim and the early Rishonim struggled with its exact meaning and purpose[2].

Halachic background – vows and oaths

In earlier times, much more so than today, individuals were inclined to “accept upon themselves” different types of self-imposed obligations or restrictions. In order to ensure that these would actually be kept, people would label their self-imposed obligation as either a neder, a vow, or a shevuah, an oath, thus giving it legal force. The binding status of vows and oaths and the horrific and tragic consequences of violating them are discussed in several places in the Torah and Rabbinic literature[3].

But the Torah also recognizes that sometimes these vows and oaths were undertaken without due consideration of the consequences. More often than not, the individual making the oath did not realize how difficult it would be to keep it. Sometimes, an oath was declared in anger or out of spite and eventually the individual regretted his words and wished to revoke them. To that end, the Torah provided a legal formula called hataras nedarim, allowing a petitioner to present his case before a beis din in order to find a legal loophole and extricate the petitioner from his plight. This process involves complex halachos, and indeed, not always can the court release the petitioner from his vow.

The view of the early authorities

Before beseeching God for atonement of sins on Yom Kippur, it is imperative that each individual absolve himself of any vows or oaths that he may have made and subsequently violated. The severity of violating a vow or an oath is such that it may block or interfere with the entire atonement process[4]. Consequently, one who is aware of any violations of oaths or vows that he may have committed is strongly urged to petition a Jewish court in order to find a way out of his self-imposed obligations. Indeed, it has become customary that already on erev Rosh Hashanah, all males petition a beis din for hataras nedarim.

But not everyone is familiar with the procedure of hataras nedarim, and not everyone who has violated a neder or a shevuah realizes that he has done so. To avert and to solve this problem, Kol Nidrei was instituted. Kol Nidrei declares that in case an individual made a vow or an oath during the past year and somehow forgot and violated it inadvertently, he now regrets his hasty pronouncement. In effect he tells the “court” – comprised of the chazan and two congregational leaders – that had he realized the gravity and severity of violating an oath, he would never have uttered it in the first place. He thus begs for forgiveness and understanding[5]. This explanation of Kol Nidrei, put forth by many of the early authorities and endorsed by the Rosh, fits nicely with the traditional text of Kol Nidrei, which reads, “from the last Yom Kippur until this Yom Kippur,” since we are focusing on vows and oaths which were undertaken during the past year[6].

The view of Rabbeinu Tam

Other authorities – led by Rabbeinu Tam – strongly object to this interpretation of Kol Nidrei. Basing their opinion on various halachic principles, they question if it is legally valid to perform hataras nedarim in this manner. In their view, Kol Nidrei was instituted to deal with the problem of unfulfilled vows, but from a different angle: Instead of annulling existing vows and oaths, Kol Nidrei serves as a declaration rendering invalid all future vows and oaths which may be uttered without due forethought – “null and void, without power and without standing[7].” Accordingly, the text was amended to read “from this Yom Kippur until the next Yom Kippur,” since we are referring to what may happen in the future, not to what has already happened in the past.

Which approach do we follow?

Most of the later authorities have accepted Rabbeinu Tam’s explanation of Kol Nidrei and this has become the accepted custom in most congregations[8]. Nevertheless, in deference to the first opinion, many congregations include both versions as part of the text. Thus the text in some machzorim[9] reads as follows: From the last Yom Kippur until this Yom Kippur [accounting for vows already made], and from this Yom Kippur until the next Yom Kippur [referring to future vows], etc.

It is important to note, however, that Kol Nidrei, whether referring to the past or to the future, does not give one the right to break his word. As previously explained, Kol Nidrei is valid only for additional obligations or personal restrictions that an individual undertakes of his own volition. By no means can hataras nedarim or Kol Nidrei exempt an individual from court- or beis din -imposed oaths, etc.

A practical application

As stated earlier, vows and oaths are not too common in our times. It would seem, therefore, that the halachic aspect of Kol Nidrei has little practical application. But when properly understood, Kol Nidrei can be used as a tool to rectify a fairly common halachic problem. There is a well-known ruling in the Shulchan Aruch[10] that any proper custom, once accepted and followed, may not be dropped without undergoing hataras nedarim. People who adopt even “simple” proper customs which they are not obligated to practice, such as reciting Tehillim daily, without making the bli neder (without a vow) stipulation, require hataras nedarim should they decide to discontinue their practice[11].

This is where Kol Nidrei[12] can help. As stated above, Rabbeinu Tam explained that Kol Nidrei is a declaration that invalidates the legal force of certain future vows. Contemporary poskim[13] rule that “proper customs” from which an individual wishes to absolve himself although he neglected to make the bli neder stipulation initially, are included in the Kol Nidrei declaration invalidating such vows. The “proper custom” may now be discontinued.

Rules

Since Kol Nidrei is an halachic procedure for nullifying certain, specific future vows, the following conditions must be met:

- Each individual must understand exactly what is being said during Kol Nidrei. Since a legal declaration is being made, if one does not understand what he is declaring, his statement cannot have legal force[14]. The difficult Aramaic text should, therefore, be studied and understood before Yom Kippur eve.

- Each individual must verbally recite Kol Nidrei along with the chazan. Obviously, the chazan cannot make such a declaration for anyone but himself[15]. It should not be recited in an undertone, but loudly enough for a person nearby to hear[16]. If it is whispered too softly, it may be invalid[17].

- Kol Nidrei should be recited while it is daylight, since the process of annulling vows [and the declaration of voiding them in the future] should not be done on Shabbos or Yom Tov[18].Kol Nidrei: A Symbolic Idea

The above discussion sums up the halachic analysis of Kol Nidrei. But as noted earlier, there is more to Kol Nidrei than meets the eye. If Kol Nidrei were merely a “dry” halachic procedure concerning vows and oaths, it would hardly evoke such deep emotional sentiment throughout the Jewish world. Why are the Sifrei Torah removed from the Aron ha-Kodesh, a haunting centuries-old melody chanted and an atmosphere of sanctity and awe created if all that is taking place is hataras nedarim? While the commentators offer various answers, we will quote just one, which is based on the teachings of the Zohar.

In Kabalistic teaching[19], Kol Nidrei is a plea to God to nullify His oath that He will punish or exile the Jewish people because of their sins. The Talmud (Bava Basra 74a) relates that Rabba bar Bar Chanah heard a Heavenly voice saying, “Woe is Me that I have sworn to exile My people, but now that I have sworn, who can annul it for Me?” Kol Nidrei implies that just as we seek to absolve ourselves of vows and oaths that burden us, so, too, may God annul His oath to withdraw His Presence from the Jewish people. In this sense, Kol Nidrei is a prayer and a supplication to God to quickly end the bitter exile and bring salvation to the Jewish nation. Thus, it is a very appropriate prayer for inaugurating the holiest and most awesome day of the year. It is this hidden message and prayer, cleverly camouflaged[20] by what seems to be a technical, halachic procedure, that evokes those deep emotions, and brings almost every Jew, observant or otherwise, scholar or student, to shed a tear and resolve to better his ways in the coming year, a year which we hope will bring the final redemption that we so eagerly await.

1. Shitah Mekubetzes (Nedarim 23b).

2. Indeed, some well-known Geonim, including Rav Netronai Gaon and Rav Hai Gaon, were adamantly opposed to the Kol Nidrei service and ordered their congregations to omit it entirely; see Tur, O.C. 619.

3. For a sampling see Shabbos 32b; Yevamos 109b; Nedarim 20a and 22b; Vayikra Rabbah 37:1; Koheles Rabbah 5:2; Tanchuma, Matos 1.

4. Shibbolei ha-Leket.

5. It is important to stress that, even according to this opinion, Kol Nidrei is a “last ditch effort” to guard a person from his own words and to save him from certain punishment. It is not meant as a crutch to rely on l’chatchilah.

6. According to this opinion, Kol Nidrei is similar to the first part of hataras nedarim which is recited on erev Rosh Hashanah.

7. The halachic basis for this type of declaration is in the Talmud (Nedarim 23b) and is not within the scope of this discussion. Note that according to this opinion, Kol Nidrei is similar to the second part of hataras nedarim which is recited on erev Rosh Hashanah.

8. Mishnah Berurah 619:2.

9. This “compromise text” was introduced by the Radvaz (4:33) and later adopted by Rav Y. Emdin (She’elas Yaavetz 145) and other poskim; see Kaf ha-Chayim 619:17.

10. Y.D. 214:1.

11. See The Weekly Halachah Discussion, Parashas Vayeilech, for a full discussion of this subject.

12. Or the second part of hataras nedarim on erev Rosh Hashanah. See Minchas Yitzchak 9:60, who explains why it is proper (but not obligatory) to recite both texts.

13. Rav S.Z. Auerbach in Minchas Shelomo 1:91, based on Teshuvos Shalmas Chayim 2:38. See also Yabia Omer 2:30 and 4:11-9, who relies on this as well.

14. See Chayei Adam 138:8 and Kitzur Shulchan Aruch 128:16.

15. Mishnah Berurah 619:2.

16. Shulchan Aruch Harav 619:3 based on Y.D. 211:1. On the other hand, it should also not be said too loudly, so as not to confuse the chazan and other worshippers; Mateh Efrayim 619:11.

17. Minchas Yitzchak 9:61.

18. Mishnah Berurah 619:5. Mateh Efrayim 619:11, explains that as long as Kol Nidrei begins during the daytime it does not matter if it continues into the night. [See Halichos Shelomo 1:17, note 43, where Rav S.Z. Auerbach questions the custom to recite Tefillah Zakah before Kol Nidrei, since Tefillah Zakah contains in it an acceptance of Yom Kippur.]

19. This idea is reflected in the section of the Zohar (Rav Shimon stood up…) which is recited by many individuals before Kol Nidrei.

20. Possibly, to confound the Satan.

Weekly-Halacha, Text Copyright © 2010 by Rabbi Neustadt, Dr. Jeffrey Gross and Torah.org.

Rabbi Neustadt is the Yoshev Rosh of the Vaad Harabbonim of Detroit and the Av Beis Din of the Beis Din Tzedek of Detroit. He could be reached at [email protected]