‘Vaetchanan– I beseeched.’

‘Halakhically, by what right may a person pray aloud, since we have learned from the sages that it is questionable whether a person may do so. Such loud prayer is considered presumptuous and arrogant, keeping in mind the greatness of HaShem and the insignificance of human beings. Hannah already taught us that one may pray in silence, ‘ and she spoke to her heart’ (Samuel 1, 1:13)'(Devarim Rabbah Parshah 2). Yet Eli the High Priest, who was the bearer of the tradition handed down from Moses, considered her to be drunk; since she did not pray loudly as was customary (Rashi). Should we not then rule that one should not be allowed to pray silently?

In order to resolve this question of silent or loud prayer, it is necessary to consider the roots from which the impetus to pray comes. We see that prayer flows from two sources. On the one hand, prayer may come from the outpouring of the heart that calls to God, because of an individual’s sorrow, or distress, or pain. Alternatively, prayer may be the result of knowledge, introspection and analysis. Here, the prayer pours out even though at the outset there was no intention to pray. While it is true that one requires both mind and heart to pray, nevertheless, in one case the source is the distress of the heart that awakens the mind to think the thoughts necessary for prayer, while in the other case it is the wisdom of the mind that awakens the heart to pour itself out before G-d.

The difference between silent prayer and those prayers that are said aloud may be explained by these sources from which the prayer flowed. The heart is warm, emotional and is full of religious feeling, so that the outpouring of spirituality cannot be contained within it. Moreover, the heart is extremely sensitive to human needs – material, physical and social- so that such prayer needs to be voiced aloud, even as it is written, ‘ let your hearts cry out to God’. This leads to expression through sound, voice and bodily movements in prayer. The mind, however, is cool and collected, rational and unemotional. Here there is constant intellectual analysis, unrelenting inquiry and sophisticated research, so that such prayer is hidden and not easily visible. That is why Holy People and the Righteous Ones always pray silently, without emotion and without movement. ‘I have heard that the Admor Simcha Bunem of Pyscha never moved his hands, his body or his eyes in prayer, nor ever raised his voice. My father told me that when he was ill on Rosh HaShanah and Yom Kippur, my grandfather, the great Admor Menachem Mendel of Kotsk, took him to pray together with him in his private study. He watched the Master pray without motion, movement or sound. He was like a pillar of fire and his face shone like torches; a veritable awesome angel of the Lord. This is the outpouring of the ecstasy of the mind, which is the highest form of ecstasy.’

In this way we may understand the difference between the formal and set prayers of the Amidah ordained by the Men of the Great Assembly [Anshei Knesset Hagedolah] and those intermittent or personal prayers offered by each individual according to their needs. The set prayer in the Shmoneh Esrai requires the concentration of the mind and the introspection of the intelligence, so that each brachah and brachah may be considered and may be examined, so as to consider its importance and the great loss that would occur if one had to exist without it. Such intellectual depth and serious search brings the mind to the stage where it is unable to be separated from the ideas in the each of the eighteen brachot and thereby one comes to pray. The sages taught (Talmud, Berachot, 28b) ‘ that one who makes his prayer set and time-bound, such prayer is not beseeching nor a request’. Naturally, each person fulfills their obligations and achieves their potential in such prayers, according to their intellectual ability. However, in the optional, introductory or intermittent prayers, each individual prays because of their needs, troubles and tribulations, or the needs and sorrows of family, neighbors and society. This is a function of heart and the emotions and therefore each prayer is a shout and a loud cry.

We know that prayer requires both heart and mind. Indeed, irrespective of the source this unity is achieved. The set prayers flow from the mind yet the mind affects also the heart that follows it, adding personal emotion and human warmth. When the prayers originate in the heart, they move the mind and the intellect to merge with them. So we have the Amidah recited in silence – the outpouring of the mind, and then the reader’s repetition is recited aloud. For this unity between mind and heart one requires the unity and community of purpose of communal prayer. Such unity of the worshipers is even able to unite Heaven and Earth.

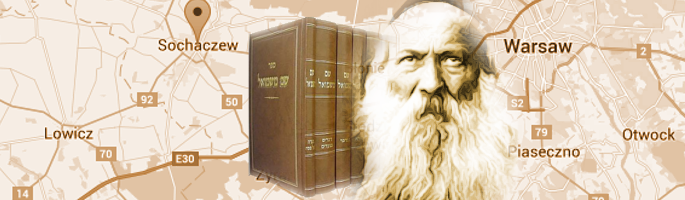

Shem Mi Shmuel, 5675.

Text Copyright © 2004 by Rabbi Meir Tamari and Torah.org.

D r. Tamari is a renowned economist, Jewish scholar, and founder of the Center For Business Ethics (www.besr.org) in Jerusalem.