When a camp goes out against your enemy, you shall guard against any evil thing.

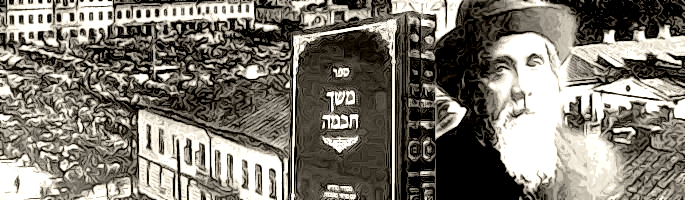

Meshech Chochmah: We are so mystified by the elliptical “evil thing” in our pasuk, that we fail to realize what the simple, basic intent is. It could very well be that the Torah here warns against inadvertently giving away strategic information to the enemy in times of war.

The Torah cautions us to limit even the possibility of any leaks. It alludes to a preference to keep the camp in a state of lock-down. No one should leave, lest that person wind up in enemy hands and convey information about the position and strength of the camp. This is why the next phrases deal with people who have no choice but to leave: those who suffered a nocturnal emission or had to respond to the call of Nature. The Torah allows this limited number of people to leave, under controlled conditions.

On the level of plain peshat, then, the evil “thing” / davar is in fact speech. This is sourced not in the similarity between davar and dibbur/ speech, but in the simple sense of the verse. Now, the Yerushalmi[2] does take our pasuk to refer to what we call lashon hora, or derogatory speech about another person. This is much less of a departure from the simple peshat than you might think. To the contrary – it flows directly. The Torah asks us to safeguard the fighting integrity of the Jewish army. Lashon hora breeds dissension and hostility between people. The Jewish fighting force aims to achieve unity of purpose and mutual devotion of its soldiers. Troops divided against themselves will be less effective, will sustain heavier casualties. The intent of our pasuk is to minimize those casualties.

Now, a usual and accepted source of the lashon hora prohibition is a different verse: “You shall not go as a gossip-mongerer among your people.”[3] The Yerushalmi must recognize two different forms of lashon hora: one inside the camp, and one outside. The former deals with speech that passes between two Jews, like the wares of the gossip-mongerer; the latter – that of our pasuk – spreads its toxins outside, away from the gaze of the community.

We find as well several methods of atonement for lashon hora, which address these two forms. The gemara[4] posits that the me’il worn by the kohen atones for lashon hora. The clanging of the bells on the hem of the me’il addresses the sound of evil speech. Another kind of lashon hora is addressed by the daily ketores. Its avodah was silent. Burning the incense did not produce the cacophony of sounds of other parts of the avodah. It was also private by nature. No one was permitted to be with the kohen inside the Heichal when he offered it. This was linked to the subtle, silent lashon hora that we call avak lashon hora – the “dust” of lashon hora, that works by innuendo, by what is not said, rather than what is enunciated.

Both of these, however, take place within the Jewish community. There is yet another form of lashon hora – that which takes place externally. No one inside finds out. This is evil speech conveyed to our enemies, away from the camp and community. Only Hashem knows about it. It is addressed by the ketores that is offered in the Holy of Holies, i.e. once a year on Yom Kippur, before Hashem, in the place that is so isolated that even the angels do not go.[5] We’ve come across it in the original encounter between the young Moshe and the two disputants, Doson and Aviram, and their implied threat to alert the Egyptians to Moshe’s killing of the Egyptian taskmaster.[6] We’ve seen it again in the gemara’s narrative[7] about Kamtza and Bar-Kamtza, and the deliberate provoking of the Roman power against the Jewish community.

Sharing community secrets with outsiders often results in a chilul Hashem, a desecration of G-d’s Name. This is an aveirah so serious, that it is one of the few for which Hashem punishes even the thought and plan, even if unaccompanied by a deed. Idolatry is treated this way;[8] all the more so chilul Hashem.

We now understand that the Kodesh Ha-Kodoshim is the private place where even the most private, unknown aveiros can find atonement. This explains to us why the Kohen Gadol could not serve in his gold garments when entering it. One opinion[9] attributes this to gaavah, to the pride that the kohen bedecked in such finery might feel. But gaavah is a feeling, a thought, not an active aveirah. Must the kohen worry about this more than any other time?

The point is that in the Kodesh Ha-Kodoshim indeed he must. There, in the intimate presence of the Shechinah, even matters of private thought stand scrutinized by Hashem, and put him in danger.