Pestilence comes to the world for death penalties mentioned in the Torah which are not in the hands of the courts [to administer] and for [the forbidden use of] Sabbatical year produce. The sword comes to the world for the delay of justice, the perversion of justice, and for those who expound the Torah not in accordance with Jewish law. Wild beasts come to the world for false oaths and the desecration of G-d’s Name. Exile comes to the world for idolatry, adultery, murder, and the working of the earth on the Sabbatical year.

This mishna is a continuation of the previous. The previous mishna began a list of seven types of punishments for various transgressions and enumerated the first three. This mishna continues with the remaining four punishments. As we will continue to see, G-d does not merely punish; He instructs. G-d, in His infinite wisdom, punishes in such a way as to reveal the true nature of the evil perpetrated, truly instructing and admonishing us to mend our ways.

The first punishment listed is pestilence. It is meted out for acts punishable by death but which the courts are unauthorized to judge. This may occur in times and places in which Jewish courts are not functional, where there is insufficient evidence to deliver a guilty verdict, or for sins for which the Torah prescribes death at the hands of Heaven rather than the hands of man.

Pestilence is also meted out for the misuse of seventh year fruit. The Torah prescribes a seven year agricultural cycle in the Land of Israel. For the first six years of the cycle, various tithes were given to the Priests, Levites and poor, depending upon the year. The seventh year of the cycle, known as the Shemitah year (literally, the “slipping away” year), is the culmination. It is a year in which it is forbidden to cultivate the fields, and produce which grows spontaneously attains a level of sanctity. Such produce does not belong to anyone: G-d reminds us that our fields are not truly ours. The field’s owner can take a portion of it into his home for personal use, but most of it is left in the field, available to strangers and animals, both wild and domesticated.

In addition, such produce must be treated in accordance with its sanctity. It may not be wasted or consumed in an unusual manner, and it cannot be sold for profit (even after a person acquires it from its “ownerless” state in the field).

(There is an additional Rabbinical decree forbidding the produce of all annuals (plants which live only one year or season) for fear that people would plant them and claim they grew spontaneously. There’s also a more recent (and relevant) dispute regarding produce grown by Gentiles in the Holy Land, if that too has sanctity. Needless to say, in modern Israel there has been a great revival of and renewed interest in what for millennia had been a scholarly, academic topic.)

This mishna refers to the misuse of seventh year produce through acts such as hoarding it or doing business with it. Such is a denial of the sacred nature of such produce. It is a form of treating the sacred as mundane, ignoring the fact that G-d imbues this world with sanctity, and of shirking our obligation to use G-d’s world in the manner He prescribed.

Pestilence is an unusual sort of punishment — at least for a G-d of absolute justice. Epidemics typically affect entire geographical areas. A large number of people in a single area may suffer — the good, the bad, and the indifferent. Justice seems to be indiscriminate, not — as we would expect — fine-tuned to the precise needs of each individual.

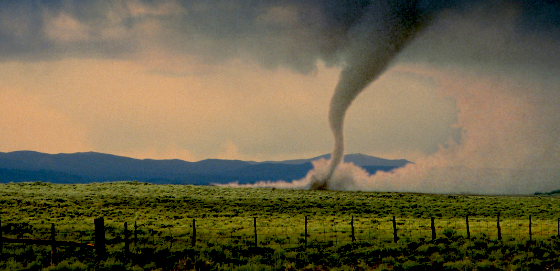

The Sages state similarly: “When destructive forces are given permission to smite, they do not distinguish between righteous and wicked” (Mechilta 11). If so, we should be surprised that a G-d of absolute justice sometimes strikes man with plague and epidemic (as well as hurricanes, tsunamis, earthquakes, etc.). Wouldn’t we expect G-d’s justice to be precise and discriminating, involving “pinpoint attacks” against the deserving alone?

In truth, G-d never strikes someone who is entirely undeserving. If a person fully deserves to live, he or she will be spared regardless of the danger surrounding him. If so, why do epidemics, as well as other catastrophes, kill vast numbers of people at once — many of whose sin seems to have been nothing more than being in the wrong place at the wrong time? Do we have to say that every single person struck by pestilence was a sinner in secret? Or must we say — as the Sages imply above — that G-d sometimes punishes in broad strokes, sweeping away innocents in the process?

This difficulty can be explained (to a small degree) through the concept known as G-d’s slowness to anger. Consider the following scenario: Person A is a perfectly okay human being. He has his own share of faults and failings — as do we all — but he is hardly a person G-d would strike down as a sinner. However, let’s say person A lives in city X, whose residents are all succumbing to a highly-contagious disease. There’s a 95% chance that anyone who drinks the water of city X will catch disease Q (hope this multi-variable math isn’t scaring anyone off). 😉 Now, person A isn’t perfect. He has many outstanding sins for which he must one day make amends. Will G-d, so to speak, “go out of His way” to save person A?

This enters the realm of G-d’s “patience”. G-d ordinarily grants us long lifetimes to improve ourselves and come closer to Him. Yet more often than not, we fail to use our lives in the manner we should: We leave G-d many outstanding debts. Nevertheless, G-d is not so quick to demand compensation: we live in constant overdraft. We learned earlier, “Whoever wants to borrow may come borrow” (3:20). G-d often waits a lifetime, using His many messengers to gradually coax us and cajole us to repentance.

Assume, however, such a person enters city X. If the (G-d-created) laws of nature would have such a person die, G-d will most likely not bend those laws in order to save him. G-d allows the world to run according to nature. If He sees to it that pestilence or some other disaster strike, only the truly righteous will survive.

Presented above was only one of many approaches to the perennial question of why the good suffer. We’ve discussed this at greater length in the past (see for example 3:19), and I won’t pretend any of us would be satisfied with today’s approach alone — although it certainly provides us with some valuable food for thought. Nevertheless, for our present purposes, I’d like to leave this issue aside in the interests of moving on. Right now we have a more basic question to deal with, which I’d like to raise today and then save for the next installment.

Even if we accept the above premise — that G-d applies far more justice than is readily evident even during times of catastrophe, why in the first place does G-d wield such destructive weapons? Why bring about a plague — one which endangers so many “innocents” — people who, while not perfect, would have otherwise been granted many more years of life? It is almost as if G-d is lashing out in uncontrolled anger at everyone and everything around. What is the perfect justice behind such seemingly erratic behavior?

A closer look at the sins of our mishna holds the key to the answer. We will pick this up G-d willing next week. Stay tuned! 🙂

Text Copyright © 2005 by Rabbi Dovid Rosenfeld and Torah.org.