We often speak about doing things “for their own sake” as a positive trait. Ideally one should give generously to charity because it is a great thing to give, not in order to be celebrated and honored for generosity. One should learn Torah for its own sake, not to be recognized as a scholar. This week, though, we learn that misbehavior can also be done “for its own sake,” and this is a terrible habit to develop.

Our reading describes the miracle of the Mahn (Manna), the miraculous bread which G-d gave to our ancestors to eat in the desert. The People of Israel complained that they were hungry, and they were given an open miracle in return—along with instructions. They were told to gather only what they needed for the day, except on the sixth day, when they were told to gather a double portion for the Sabbath.

So everyone did what they were told to do, since it was so simple, right? Wrong! The Torah tells us that “they didn’t listen to Moses, and men left it over until morning, and it became wormy” [Ex. 16:25]. Who didn’t listen? The Medrash tells us that those who gathered extra Mahn were Dasan and Aviram.

Who were they, and, in modern language, what was their problem? There is no question that the Mahn was miraculous. The Commandment was simple and straightforward. Why, then, would anyone disobey?

We first meet Dasan and Aviram much earlier in Sh’mos, the Book of Exodus. Moses goes out and sees an Egyptian beating a Jew, and in order to protect his brother from death, he kills the Egyptian [see Ex. 2:12-14]. The next day, he finds two men fighting with each other, and he says to the attacker, why are you hitting your friend?

That attacker answers back, “who made you ruler and judge over us? Are you saying you’re going to kill me like you killed the Egyptian?” And the Medrash tells us that the two men fighting, who challenged Moshe in this way, were none other than the same Dasan and Aviram. Moshe was obviously trying to do good, and defend the Jews, but they argued with him anyway.

The Medrash also teaches that what Moses found so frightening about this exchange is that it told him there were wicked people, informers among the Jews. It was one thing to accept that Pharoah and the Egyptians were evil, and hated the Jews. But for the Jews themselves to inform on others, and do evil to their own people, was much more dangerous.

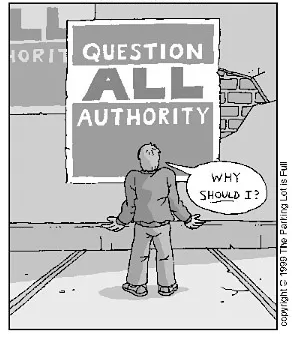

And as we see, Dasan and Aviram weren’t simply informers; they were troublemakers, people who challenged authority at every opportunity. They finally met their end during the rebellion of Korach, where one could also ask what role they had to play. Korach was jealous of Moses and Aharon for the honor they received. But if Korach had taken a leadership position instead, Dasan and Aviram would still have been simply members of the tribe of Reuven. How was this their fight?

They were obviously sincere to a certain degree, because they merited to be part of the Exodus. But they also challenged Moshe’s authority at every opportunity, apparently simply for its own sake, when they had nothing to gain. Even on something so trivial as gathering extra Mahn, they couldn’t resist seeing if they could find a flaw in the orders Moses gave them. That was the same trait that eventually led to their deaths in Korach’s rebellion.

Today we see the terrible damage done by “Jewish” groups that claim to be the authorities on good and moral conduct, and on what is or is not antisemitism, without regard for the wisdom that has been with us since Moshe himself. They live simply to challenge the authority of millennia of Jewish knowledge. And, like Dasan and Aviram, they prove much more dangerous to Jews than those who hate us from outside!

Good Shabbos,

Rabbi Yaakov Menken

![]()

Amalek and the Messiah

See it at JewishAnswers.org

Question: I know that one of Moshiach’s (Messiah) tasks is to rid the world of the nation of Amalek. Up until recently I understood this to be a literal killing of a nation who has always been our arch enemy. Recently, though, I read an opinion that states that the Amalek that we are referring to is actually the Amalek which resides inside each one of us in the form of uncertainty as the word “Amalek” in Hebrew actually means “uncertainty.” Can you explain this? Will Moshiach actually lead us to kill a nation called Amalek or is it meant figuratively? If it is literal, how are we to know which nation is actually Amalek thousands of years later?

Answer: Questions pertaining to Moshiach are from the most difficult to answer, simply because of the amount of unknown information.

What we do know about Amalek is based upon the various episodes in history that discuss Amalek. Amalek is the same numerical value as doubt (Safek), hence the idea that Amalek is rooted in doubt. Essentially, they created the initial doubt in the world about G-d’s ability to oversee the details of the Jewish People. By jumping in and attacking us after the world had witnessed all the miracles of Egypt and the Sea, they cast aspersions on the sanctity of our relationship with G-d. That is what the Midrash comments “they cooled off the bath water”, they created doubts in the minds of the nations and the Jewish People. The Almighty’s Throne will not be restored to its full glory until all doubt about His Omnipotence is eradicated. This was the task that King Shaul was to achieve and didn’t. This remains our ongoing task, removing doubt.

Whether Moshiach will literally or figuratively fight the battle, I can’t tell you. But our job is to continue to strengthen our relationship with the Almighty step by step until the goal is achieved.