The rabble that was among them cultivated a craving, and the Bnei Yisrael also wept again, saying, “Who shall feed us meat?”

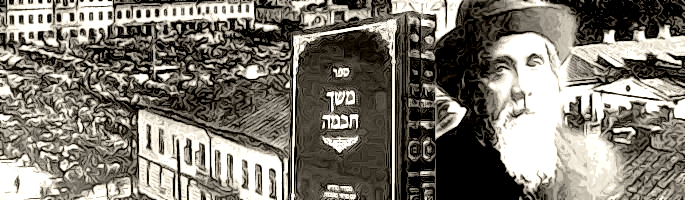

Meshech Chochmah: Short of a supply of meat, they weren’t. A surfeit of cattle[2] led to Reuven and Gad choosing to pass up their portion of the Land in favor of more appropriate grazing land on the east side of the Jordan. What they lacked was not the meat, but the ability to eat it the way they preferred, which was simply to satisfy their desire. According to R. Yishmael,[3] they were halachically constrained from consuming meat as a desirable menu item. Meat was permitted to this generation only as part of some holiness exercise, like the meat of a korban shelamim. Even those who disagree with R. Yishmael still had them (and us!) subject to innumerable laws and restrictions regarding the preparation of meat before it could be eaten. They wanted the license to eat like they had earlier in Egypt – “we remember the fish that we ate for free.”[4] As Rashi explains, free means unencumbered by the demands of any mitzvos. (Specifying fish is particularly apposite, because all of a fish is permitted – even its blood.)

We can detect another dimension in their complaint. It was, after all, the mohn that they tired of, and wished some “real” food in its place. This becomes understandable if we remember that it was Moshe’s merit that brought them the mohn,[5] which was more spiritual than material, and is called the food of the angels.[6] Food does more than sustain us. Different foods affect our personalities differently. While plants nurture forces of life and growth within us, only animal flesh carries with it craving and lust. (This is why the gemara[7] states that an ignoramus may not eat meat. Without Torah, he has no defense against the elevation of his level of desire that the meat contributes to him.)

Those who clamored for meat longed for the experience of passion and desire. The mohn was good food – perfect food, really. But they did not get from it the passion-surge that they reasoned they would get from meat. They longed for meat because they longed to experience longing!

The same phenomenon accounts for their “crying in/for their families,”[8] which the Sifrei takes to mean arayos. This may not mean classes of forbidden relationships, as it is usually understood, but the experience of lust and desire in their intimate lives. After the experience at Sinai, Moshe had become a “godly person,”[9] and separated from his wife. Typical desires had become irrelevant to him on his lofty level. They had not become irrelevant to his people, some of whom wanted to see those desires return to their previous strength and prominence.

Moshe’s superior spiritual level made him the perfect conduit to provide the spiritual food of mohn to his people. By the same reasoning, however, he was useless in providing meat that was laden with desire. He therefore registered his complaint to Hashem. “Where will I get all this meat?”[10] He knew that his merit was a mismatch for it.

Hashem had a workaround. Moshe was to gather seventy people, each one worthy of receiving some of his spirit. Great as they were, they were not clones of Moshe – nor were they close. They had not separated from their wives; they still knew the meaning of taavah. If they would elevate their inner selves to the point that they, too, could be recipients of some of a Divine spirit, they would be suitable conduits to provide meat to the people.

Moshe, however, on his greater madregah, was not capable of providing the meat.