The most successful children are not the children who come from the wealthiest homes or those who participate in the most extracurricular activities. They are not the ones who attend Ivy League colleges or those who have the most sophisticated educational toys or enjoy the most exotic vacations.

According to a celebrated study by the National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse at Columbia University, entitled “The Importance of Family Dinners” (2005) the most successful children — that is to say — the most well-adjusted, balanced, self-sufficient, and self-confident children — are the children who have dinner with their parents at least five evenings per week. Why?

When we have open communication with our children on a regular basis, when we sit with them and hear them and value their opinions, that give them the sense of inner security that we believe in them. With this foundation of security and support, they become secure enough to take risks, try to meet any challenge, and accomplish their goals. Instead of giving them instructions, arguments, and lectures while we are standing and they are sitting, or giving them last-minute reminders as they are running out the door, when we sit down and share thirty minutes of discussion through direct contact at the dinner table, our children get the sense that their parents have time for them and take them seriously. When we create consistent family time, not just occasional quality time, we are saying: “I have time for you because you are valuable to me and your views and thoughts count. Let’s talk over dinner.”

In this week’s parshah, the tribes of Reuven and Gad asked Moshe Rabbeinu for an allotment of land on the east bank of the Jordan River, because it had grazing land for their cattle. They said: “Pens for the flock shall we build here for our livestock, and cities for our small children” (Bamidbar 32:16).

Rashi comments:

They were concerned for their property more than they were for their sons and daughters, for they made mention of their livestock before their children. Moshe told them: This is not right. Make that which is essential, essential and that which is secondary, secondary. First build cities for your children and then enclosures for your flocks.Children first, work second.

In our own lives, do we work to live or do we live to work?

When I was in law school in Toronto, one night I was coming home from the library. On the subway I met an older friend who was already working as a lawyer, coming home late from work. I was shocked to see lawyers working so late. My friend held up two briefcases and told me that he was even bringing work home from the office. “This briefcase is for Chani and this briefcase is for Esti,” he told me proudly. I said to myself: His kids will be long asleep when he gets home, so he won’t see them. And even if they were awake, he wouldn’t have time to spend with them, because he would be too busy with his work. What is the point of “working for your children” if you never see them?

True, we have to make a living. And yet, I would like to see that one child, so many generations in the future, that all of his ancestors were “working for.” Would that child be the happiest and wealthiest child in the world, provided with all the things his parents never had? Or would he be standing by the window, a ball in his hand, hoping that his father would have time to play with him?

Shlomo HaMelech says, “Teach a child according to his way, so that when he becomes old he shall not depart from it” (Mishlei 22:6). In order to know “a child’s way,” we need to spend real time with that child. We must make ourselves accessible to talk and share time with the child. We need to get down on the floor with our children to discover their thoughts, questions, interests, and fears. They will open up and communicate only if they feel comfortable and secure in their relationship with us. In other words, they have to trust us. For trust to develop and for them to want to follow in our ways and traditions, we need to discover their uniqueness — their interests and ways of learning.

The Alter of Slobodka points out that both child and aged scholar learn the words of the Torah: Torah tziva lanu Moshe. Each learns Torah at a different level of depth according to his understanding. The Alter implies that the only way the child will still be inclined to learn those same words when he becomes old is if he began learning those words early, when he began to speak.

How do we relate to children when they are young? With sweetness and gentleness. We sit closely to our children, speak softly to them, hug them while we learn with them, and introduce them to Torah gently, with love and affection. That is “his way,” the need, of a young child. In this way our children will come to associate learning Torah with love. Judaism to them will mean an avodah of love, and even when he gets older “he will not depart from it.” We must strive to teach it and live it with attention, respect, and love — and they will want to continue learning when they are old.

BRING IT HOME

In our lives, we must determine our priorities — children first, work second. We work to live, not live to work.

One of the most important ingredients in producing successful children is regular family time — for example, at mealtimes.

Family time allows children to feel that they are important enough for you to actually spend time talking, playing, and relaxing with them. Encourage your child to voice her opinions, and show that you value and validate those opinions through respectful discussion.

The more floor time we spend with our children, the more likely they will open up and share their feelings and fears with you. If you come down to their level, they will level with you.

Learning sessions with our children must be positive, loving experiences. Put your arm around your child and smile while you are learning with him. In this way children will come to love learning, because they will associate it with love and affection.

(Drawn from the essay “HaSheleimus Tamid B’Reishisah” in the Ohr HaTzafun by the Alter of Slobodka)

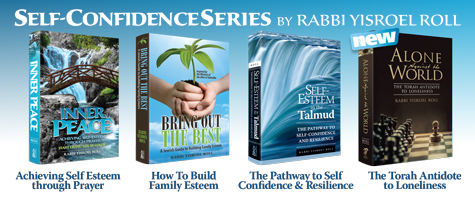

This essay is an excerpt from Bring out the Best-The Jewish Guide to Build Family Esteem by Rabbi Yisroel Roll. Click here for details.http://www.feldheim.com/catalogsearch/result/?q=Yisroel+Roll