Friday Night

ON ONE HAND I’d rather not talk about it, especially so soon after it happened. I do not know all the facts, nor can we know all of them. Our insatiable need for meaning, especially when it comes to tragedy, compels us to look for it everywhere we can. But without prophecy, who can really know why God does what He does, and why one person is saved when another is not?

On the other hand, it doesn’t seem right not to say something, and act as if it is business as usual when it clearly is not. It is like what happened when Nadav and Avihu died, when the Jewish people went from the heights of spiritual celebration to the depths of tragic mourning. The video clip taken right before the catastrophe in Meron shows an area packed with Jews feeling tremendous achdus and singing heartfully for the coming of Moshiach. It makes this even more painful.

Some would argue that this was an accident waiting to happen, that the potential for it to occur has been there every year. The safety conditions were not great, especially during the time of Corona and at a time that mutations are making rounds. It’s as if the miracle simply ran out.

The Gemora says that during the years of Rebi Elazar ben Shimon’s suffering, no one died prematurely (Bava Metzia 85a). But how does the Talmud even know this, when it says that one’s day of death is a secret not shared with man (Shabbos 153a)? It also says that Moshe died earlier than he should have though he lived exactly 120 years, something that was decreed back in Noach’s time (Sha’ar Hapesukim, Noach).

In Sha’ar Hagilgulim it says that people die “young” because their soul has finished its rectification for that lifetime. Since it cannot get its next level without first dying and reincarnating, they are taken “early” for their own benefit, so they can get on with their overall tikun.

But their family does not know this. As far as parents are concerned, their child is destined to live a full lifetime, to grow up, mature, marry, and have a family of their own. We always worry about the safety of our loved ones, but do not anticipate those concerns coming true. Certainly not when those loved ones go to a Lag B’omer gathering at the kever of one of the greatest tzaddikim to have ever lived, on his very yahrzeit…on a day that also marks the time Rebi Akiva’s talmidim stopped dying. May God comfort all of them.

I once spoke to someone who told me that he adds to the list of his daily prayers that when his time comes, God should take him while in the middle of doing a mitzvah. He said that he hoped it would be while in the middle of the Shemonah Esrai, while praying with a lot intention, and ideally, during the blessing that praises God. One of his greatest fears is not dying, but breathing his final breath while doing something meaningless.

Even the evil Bilaam came to appreciate this idea, with the help of prophecy, saying:

“May my soul die the death of the upright and let my end be like his.” (Bamidbar 23:110)

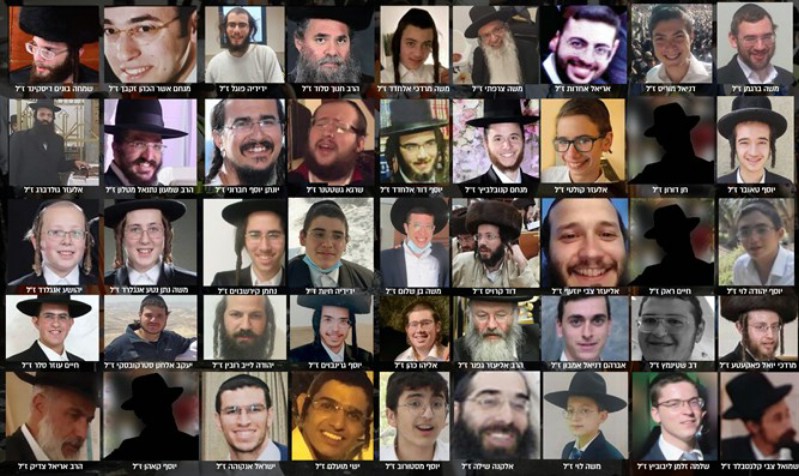

Maybe the miracle simply ran out. Or maybe God has something else in mind yet to unfold, and it just cost us the lives of these elevated 45 souls. “Eretz Yisroel,” it has been said, “was built on the ashes of the Holocaust.” There will be discussions about safety. There will be finger pointing to distribute the blame. There will be criticism about the behavior of those involved directly and indirectly. But how many people will rise above all of it, and accept that the cheshbonos of God are beyond us?

Shabbos Day

THE SECOND HALF of this week’s reading is Parashas Bechukosai with its blessings for obedience and its 49 curses for disobedience. The Talmud teaches that God works middah-k’neged-middah, measure-for-measure (Sanhedrin 90a). A Torah Jew is raised with the idea that getting good usually means we have done good, and getting bad usually means that we have acted badly.

Hester panim, when God hides His face from us, does not mean that the rule changes, as Rashi explains. It just means that we won’t be able to see how the “measure” we received was in response to the “measure” that we did. But as the Talmud says, God is not a vatran, meaning He never usually ignores the thing we do right or wrong. If He does, that person is in worse shape than the one getting punished.

So when 45 people die “tragically,” many naturally assume that someone is being punished for something. Nadav and Avihu may have been greater than Moshe and Aharon, but the Talmud cites at least three reasons why they warranted death. As the Talmud states, God deals with righteous people to a hairsbreadth (Bava Kamma 50a), making insignificant sins to us reprehensible sins to God.

Chizkiah Hamelech almost died in this world and the next one because he held off having children (Brochos 10a). And it wasn’t as if he didn’t want to have children so he could travel lighter, like many today. He had learned through prophecy that his son would turn the nation to idol worship, and had denied himself the mitzvah and pleasure of fathering children to save the nation.

And yet God’s response was not only to cut Chizkiah—the man who was almost Moshiach (Sanhedrin 94a) — down in this world, but to cut him off from the next world as well! After being told that he was wrong to try and second-guess God by Yeshaya Hanavi, he did marry and fathered Menashe who, as prophesied, turned the nation to idol worship.

Aharon had it right. After his two sons died before his very eyes, and though Moshe consoled him by speaking highly of them, Aharon chose silence as his response. Yes, his sons had erred gravely, but he too had made the mistake of being involved with the golden calf, even though he had done it for all the right reasons. In fact, he may have known that all four of his sons were supposed to have died, and would have had it not been for the prayer of Moshe.

The bottom line? There were a bunch of straws on the camel’s back, and who knows which one broke it? And when you factor in concepts like “alilus” and similar ideas that emphasize the hidden and mysterious ways of God, is there any better response than silence?

The blessings and the curses teach us that God takes note of and cares about what we do, so we should as well. But by no means do they open a clear view of God’s reactions to the actions of man. The only clear thing we can count on with complete faith is that everything God does is just and good (Brochos 61b). Not because we believe blindly, but because God made a point of telling us, and that He showed us that this is true (Devarim 4:35).

What happened in Meron on Lag B’omer, like every last thing in history, was set in motion at Ma’aseh Bereishis. Forty-five people were meant to die as they did. And God, being above time, even knew which 45 people specifically would die that day, at the precise moment they did. Not knowing this, and not even suspecting it would happen, we can only experience shock and great sadness. We are forced to call upon levels of emunah we haven’t had to for some time now, especially the families and friends directly affected.

Seudas Shlishis

THE OTHER THING people forget to do is consider the “Big Picture.” Life is so involving, so incredibly distracting, that we lose sight of the overall plan for Creation. This year is 5781. The Roman Exile began around 3698, over 2,000 years ago. To us that is ancient history, but to history it was the beginning of the fourth and final exile that we are now in the process of completing. We’re as connected to that time period as we are to the one just before our own. It’s all one history.

But why stop there? The Roman Exile is just one of the four hinted to in the second verse of the Creation story, the one about null and void, etc. What happened last week in Meron, and countless other places around the world we don’t even know about, is rooted in that second verse about Creation.

But why stop there? Everything that goes wrong in history is rooted in what went “wrong” in history before our world even began. Even the Talmud talks about the “974 Generations” that “existed” prior to Creation, though it seems from the Talmud that they never really existed until after Creation (Shabbos 88b; Chagigah 13b).

Kabbalah says differently. According to Kabbalah, not only did the 974 Generations exist, but they were the first to actualize evil, making possible the sin of Adam Harishon and expulsion from Paradise. Expulsion made possible the world we now know in which God’s Presence seems to fluctuate, confusion seems to reign, and all kinds of things go wrong in every generation since.

That’s why, as the verse says at the beginning of Behar, God took us out of Egypt to bring us to Eretz Canaan, to be our God. From Day One history has been about Tikun Olam—World Rectification. And once Adam failed to do that, a story unto itself, then history just seemed to whip about like a hose pipe that has gotten out of hand. The question since then has not been, “Why did that bad thing happen?” but, “How come more bad things haven’t happened?”

Melave Malkah

WHEN A WATER pipe bursts, it usually catches us by surprise. Since the walls of the pipe do such a good job at keeping the water inside contained, we forget about the pressure they “feel” moment-to-moment from the water inside. The walls say, “No, no, no, we must not let you go!” but the water says, “Yes, yes, yes, we will burst through you with much stress!”

History is the water in the pipe, crazily anxious to fix the world and bring Moshiach. It only knows exile and redemption, hates the former and yearns for the latter. If only we could say the same thing about ourselves.

But we can’t. For reasons we cannot control, and for some that we can, we lose our focus. One of the most uplifting things about being exposed to Kabbalah, is how it helps a person to remain focused on the BIG Picture, on the need to end exile and actualize redemption, even while enjoying the niceties of the world. It reminds you about the pressure inside the “pipe,” and makes you wary of potential “leaks.”

I particularly found it moving to hear those at Meron singing in unison about awaiting Moshiach’s arrival. It was one of those moments, one of those rare moments these days, when people were focused on the right thing. I didn’t wonder how this could happen to them because of it, but it occurred to me that it specifically happened because of it. It was as if it made them fitting more than everyone else that day to become the missing sacrifice to greatly further the cause of redemption.

I’m not saying that this is what happened. Vayidom Aharon—and Aharon was quiet. I’m just wondering out loud, not because I need to find meaning in tragedy, because we have emunah for that, and “All that God does, He does for the good.” I am just saying that big events such as this one do not belong to our narrow-minded subjective realities of everyday life. They belong to a much larger picture of history that most people do not even recognize…but really ought to.

May God comfort all the families and friends of those who have suffered, which should be all of us on some level, and may the loss signal the imminent arrival of Moshiach Tzidkaynu and Geulah Shlaimah.

Note: I have, with the help of God, just completed my translation of Vayikra, Bamidbar, and Devarim of Sha’ar Hapesukim, and have decided to dedicate it in memory of those who died in Meron, especially since I finished on the same day. It was suggested to me that others might want to have a part in this, which they can do by using this link: https://www.paypal.com/donate?hosted_button_id=JNTUTEMPJ9QBU. Money dedicated will be passed on to funds set for families directly affected by the tragedy.