The main thrust of sefirat ha’omer is during the period till Lag B’omer. Now sefirah comes to purify the animal nefesh, that is the nature of Man and his midot, so that we can pursue Hashem even when there is not the clear mind and intelligence to light our way. That is why we start counting le macharat hashabbat and not on the first day of Pesach itself. On the chag proper all the great spiritual lights are glowing so that all our desires and midot subject themselves to Hashem. However, when Yom Tov passes those great lights are removed and we return to the usual pettiness of mind. Only then is the appropriate time for sefirah, as it is written, ‘When I sit in darkness, Hashem is a light for Me’ (Micah, 7:8). This is the desired achievement for Man; that even his body should be sanctified and holy without the guidance of his mind. It is the appropriate preparation for Shavuot, since to the same extent and effort that one is drawn to Hashem with the body only, the great spiritual light of Torah pour down on him.

Just as in the physical world, the light of day starts to be reflected during the 3rd watch of the night, so it is in the spiritual. The first two-thirds of Sefirah when the major influence is that of Pesach with its redemption from slavery and physical hardship, are primarily days of darkness and night. However, during the last third of the sefirah days, starting with Lag B’omer when our preoccupation with petty matters declines and the orientation is towards Shavuot and the spirituality of Matan Torah, the great spiritual light begins to be reflected.

The plague in which the 25,000 disciples of Rabbi Akiva died and its cessation on Lag B’ Omer [Talmud Bavli, Yevamot 62b] is explained by the nature of the period of Sefirat HaOmer in which it occurred and the significance of this day on which it ceased. So too, this will help us understand the Talmudic explanation that they died as a punishment for not giving each other proper respect, even though this is not a sin for which there is a death penalty, either by a human bet din or at the hand of Heaven.

Sefirat Ha Omer is meant to enable us to purify the animal characteristics within us and to make them holy, a human yearning and trait beyond the perspectives of rational thought and intelligence. In order to do this, we are required to negate the ‘yesh’, our spiritual and material possessions that are the essence of our individuality. The two mitzvoth in connection with the bringing of the Omer are both indicators of that individuality.

The sacrifice brought on that day is of barley, primarily food for animals in contrast to wheat. Furthermore, the use of the products of the new harvest [Chodosh] is only permitted after the bringing of the omer. This is an acknowledgement of the Divine source of material wealth, even though such wealth is morally and legally the property of the human owner. Omer was brought not on Pesach itself but rather on the first day of Chol HaMoed. After all, the Chag by its very nature brings the subjection of all our human desires and mental or physical needs to the service of HaShem. It needed to be brought on Chol HaMoed in which there is partial satisfaction of our material and physical needs and wants, to demonstrate the sanctification and elevation of these needs and desires.

Both Pesach and Shavuot flow from the importance of ‘ klall Yisrael’. ‘A priori, the korban pesach should not be brought by an individual’ [Mishneh Torah, Hilkhot Korban Pesach, chapter 2, halakhah 2], and the word Omer, has its roots in â??ingathering. On Shavouot, all the souls gathered together. So the appropriate preparation for Shavout is to make all our material possessions and our very bodies holy, even beyond the instructions of our minds. In consequence of our preparation, an abundance of great light and Torah are poured out over us on Shavout The efforts made during this first period of sefirah, enable everyone to negate part of their own personal value and abilities, the spiritual and material ‘yesh’, and thereby to perceive and accept those of others. Thereby we are able to come to the unity and the formation of a single personality that are a prerequisite for receiving Torah. The Torah [Shmot, 19:2] uses the singular form to describe the encampment at the foot of Sinai on Shavuot. Rabbi Menachem Mendel of Kotsk, taught that the verse, ‘ I stood between you and G-d’, [Moshe’s description of Sinai, – Devarim,5:5 ], means that it is the individual ‘ I- Anochi ‘ that stands between us and G-d.

The disciples of Rabbi Akiva were according to the Zohar, given the task of redeeming the sin of the tribe of Shimon and its Nasi, Zimri at Shittim for which 25,00 died. The disciples needed to negate their own individual value and give honor to that of others in order to achieve this, as this was actually the cause of the sinning, since at Shittim they put their personal lusts and desires in place of the welfare and spiritual good of Israel. Yet Rabbi Akiva’s students were unable to achieve such negation so they failed to redeem the sin that had caused death and therefore they too had to die.

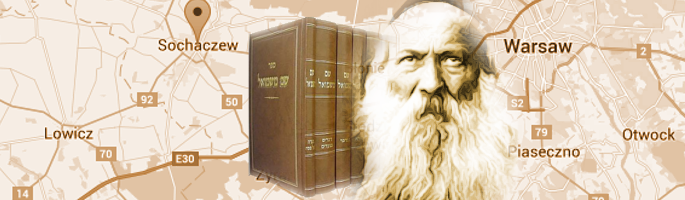

(Shem Mi Shmuel, Sefirat Ha Omer, Pesach Haggadah; Emor, 5671,Lag Ba Omer. For a fuller discussion of the sin at Shittim, see Shem Mi Shmuel, Balak, 5679).

Elsewhere the Shem Mi Shmuel explains the â??sinat chinam’ that led to the Churban Bayit Sheni in a similar fashion. The Talmud, using the verse ‘Why was the Land destroyed?’ (Yirmiyahu, 9: 11) as its base, comments that it was because the scholars of the Second Temple did not recite the blessing that we say before reading from the Torah ‘Who gives us the Torah’ Bava Metzia 85b). Says the Shem Mi Shmuel ‘Although they studied much Torah diligently, they forgot that there is a Giver of the Torah’. A parallel perhaps to the students of Rabbi Akiva, who because of their intense learning could not give honor and respect to each others ideas and learning.

Text Copyright © 2004 by Rabbi Meir Tamari and Torah.org.

D r. Tamari is a renowned economist, Jewish scholar, and founder of the Center For Business Ethics (www.besr.org) in Jerusalem.