King David had many challenges throughout his life. What caused King David to to be shunned by his own brothers in his home (Tehillim Chapter 22:9: “I have become a stranger to my brothers”), by the Torah Sages who sat in judgment at the gates (Tehillim Chapter 22:19 “those who sit by the gate talk about me”) and by the drunkards on the street corners (Tehillim Chapter 22:19: “I am the taunt of drunkards”). What had King David done to arouse such contempt?

This psalm, (Chapter 22) in which King David passionately gives voice to the heaviest burdens of his soul, refers to a period of twenty-eight years, from his earliest childhood until he was crowned king of the people of Israel, by the navi, Shmuel.

David was born into the illustrious family of Yishai, who served as the head of the Sanhedrin–Supreme Court of Torah law, and was one of the most distinguished leaders of his generation. Yishai was a man of such greatness that the Talmud [1] observes that, “Yishai was one of only four righteous individuals who died solely due to the snake of the Garden of Eden”—i.e., only because death was decreed upon the humankind when Adam and Eve ate of the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil at the snakes’s seduction, not due to any sin or flaw of his own. David was the youngest in his family, which included seven other illustrious and accomplished brothers.

Yet, when David was born, this prominent family greeted his birth with contempt. As David describes in the psalm, “I was a stranger to my brothers, a foreigner to my mother’s sons . . . they put gall in my meal, and gave me vinegar to quench my thirst.”

David was not permitted to eat with the rest of his family, but was assigned to a separate table in the corner. He was given the job of shepherd, because “they hoped that a wild beast would come and kill him while he was performing his duties,” [2] and for this reason was sent to pasture the sheep in dangerous areas populated by lions and bears, as the navi states: And David said unto Shaul: ‘Your servant kept his father’s sheep; and when there came a lion, or a bear, and took a lamb out of the flock I went out after it, and smote it, and delivered the lamb out of his mouth; and when the lion arose against me, I caught it by its beard, and smote it, and slew it. Shmuel 1, 17:34-35

Only one individual throughout David’s life was pained by his unjustified plight, and felt a deep and unconditional empathy for the child whom she alone knew was undoubtedly pure. This was King David’s mother, Nitzevet bas Adael, who felt the intensity of her youngest child’s pain and rejection, as her own. Torn and anguished by David’s unwarranted degradation, yet powerless to stop it, Nitzevet stood by the sidelines, in solidarity with him, shunned herself, as she too cried rivers of tears, awaiting the time when justice would be served. It would take twenty-eight long years of isolation, rejection, suffering and degradation, until that justice would finally begin to materialize.

Why was the young David so reviled by his brothers and people? The medrash explains [3] that David’s father, Yishai, was the grandson of Boaz and Ruth. After several years of marriage to his wife, Nitzevet, and after having raised several virtuous children, Yishai began to entertain personal doubts about his ancestry. True, he was the leading Torah authority of his day, but his grandmother Rus, was a convert from the nation of Moab, as related in the book of Rus.

During Rus’ lifetime, many individuals were doubtful about the legitimacy of her marriage to Boaz. The Torah specifically forbids an Israelite to marry a Moabite convert, since this is the nation that cruelly refused the Jewish people passage through their land, or food and drink to purchase, when they wandered in the desert after being freed from Egypt.

Boaz and the Sages understood this law—as per the classic interpretation transmitted in the “Oral Torah”—as forbidding intermarriage with converted male Moabites, who were the ones responsible for the cruel conduct, while exempting female Moabite converts. With his marriage to Ruth, Boaz hoped to clarify and publicize this Torah law, which was still unknown to the masses. [4]

Boaz died the night after his marriage with Ruth. The night before Boaz’ death, Ruth had conceived and subsequently gave birth to their son Oved, the father of Yishai. Some doubters at the time claimed that Boaz’s death verified that his marriage to Ruth the Moabite had indeed been forbidden.

Time would prove differently. Once Oved (so called because he was a true oved, servant of God), and later Yishai and his offspring, were born, their righteous conduct and prestigious positions proved the legitimacy of their ancestry. It was impossible that men of such caliber could have descended from a forbidden union.

However, later in his life, doubt gripped at Yishai’s heart, gnawing away at the very core of his identity. Being the sincere individual that he was, his integrity compelled him to act. If Yishai’s status was questionable, he was not permitted to remain married to his wife, a veritable Israelite. Disregarding the personal sacrifice, Yishai decided the only solution would be to separate from her, no longer engaging in marital relations. Yishai’s children were aware of this separation.

After a number of years had passed, Yishai longed for a child whose ancestry would be unquestionable. His plan was to engage in relations with his Canaanite maidservant. He said to her: “I will be freeing you, conditionally. If my status as a Jew is legitimate, then you are freed as a proper Jewish convert to marry me. If, however, my status is blemished and I have the legal status of a Moabite convert forbidden to marry an Israelite, I am not giving you your freedom; but as a shifchah k’naanis, a Canaanite maidservant, you may marry a Moabite convert; namely, me.”

The maidservant was aware of the anguish of her mistress, Nitzevet. She understood her pain in being separated from her husband for so many years. She knew, as well, of Nitzevet’s longing for more children. The empathic maidservant secretly approached Nitzevet, and informed her of Yishai’s plan, suggesting a bold counterplan. “Let us learn from your ancestress and replicate their actions. Switch places with me tonight, just as Leah did with Rachel,” she advised.

Nitzevet took the place of her maidservant. That night, Nitzevet conceived. Yishai remained unaware of the switch. The Talmud states: The mother of David was named Nizevet, the daughter of Adael.[5]

After three months, Nitzevet’s pregnancy became obvious. Incensed, her sons wished to have their apparently adulterous mother executed, together with the “illegitimate” fetus that she carried. Nitzevet, for her part, would not embarrass her husband by revealing the truth of what had occurred. Like her ancestress Tamar, who was prepared to be burned alive rather than embarrass Yehudah, (Breishis 38) Nitzevet chose a vow of silence. And like Tamar, Nitzevet would be rewarded for her silence with a child of greatness who would be the forebear of Mashiach.

Unaware of the truth behind his wife’s pregnancy, but having compassion on her, Yishai ordered his sons not to touch her. “Do not kill her! Instead, let the child that will be born be treated as a lowly, and despised servant. In this way everyone will realize that his status is questionable and, as an illegitimate child, he will not marry an Israelite.”

From the time of his birth onwards, then, Nitzevet’s son, David, was treated by his brothers as an abominable outcast. [6]

Noting the conduct of his brothers, the rest of the community assumed that this lad was a treacherous sinner, full of unspeakable guilt. On the infrequent occasions that Nitzevet’s son would return from the pastures to his home in Beit Lechem, he was shunned by the townspeople. If something was lost or stolen, he was accused as the natural culprit, and ordered, in the words of the psalm, to “repay what I have not stolen.”

Eventually, the entire lineage of Yishai was questioned, as well as the basis of the original law of the Moabite convert. People claimed that all the positive qualities of Boaz became manifest in Yishai and his illustrious seven sons, while all the negative character traits from Ruth the Moabite clung to this despicable youngest son.

[1] Shabbos 55b

[2] Sifsei Kohen, VaYeishev

[3] Yalkut HaMachiri, and Sefer HaTodaah, Sivan and Shavuot

[4] Yevamos 48a

[5] Bava Basra 91a

[6] In the verse in the psalm where David says he was a “stranger” to his brothers, the Hebrew word for stranger, muzar, is from the same root as mamzer—illegitimate offspring.

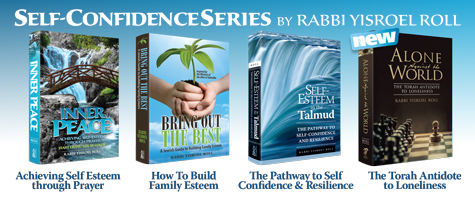

This essay is an excerpt from Rabbi Roll’s book, Alone Against the World. http://www.feldheim.com/catalogsearch/result/?q=yisroel+roll