Rather to my land and to the place of my birth you shall go, and take a wife for my son, for Yitzchok.

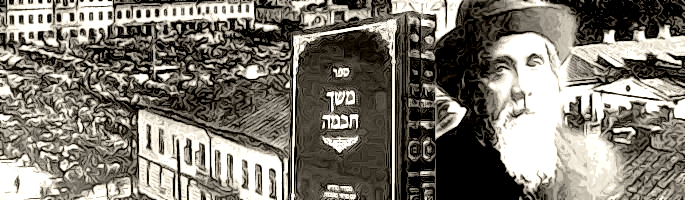

Meshech Chochmah: “My land” is a bit of a stretch. Avraham had turned his back on it decades ago, when Hashem told him to leave it all behind and move to Eretz Yisrael. In what way did Avraham relate to it as “his” land?

Avraham had in mind something much more important than nostalgia for a country he had once called home. He alluded to the future conquest of Syria by Dovid. At that time, Avraham would be able to truly call Aram Naharaim “my land.” Eliezer would tactfully not make reference to this allusion, not wishing to take any chance about antagonizing Besuel and Lavan, who might resent such grandiose forecasts about the future. Eliezer wasn’t taking any chances about jeopardizing the shidduch. He therefore skipped that part of Avraham’s instructions, and spoke only about his father’s house and my family.[2]

It is also possible that Eliezer used his blue pencil even more dramatically than we thought. He not only left out crucial details when necessary, he enhanced the story by manufacturing a few himself. It might very well be that Avraham told Eliezer nothing at all about turning to his closer family. He may have said nothing more than what is contained in our pasuk, namely to go to the region of his origin, and the people in his extended family in the place of his birth. Avraham never insisted that spousal candidates for Yitzchok come from his immediate family.

Given all that latitude, Eliezer chose a reasonable test to identify suitable candidates through demonstrating great chesed. There was no divination involved in this at all, saving us from the trouble of dealing with what has looked to others like a form of nichush, of prognostication that the Torah forbids. It was Eliezer who massaged the story when he presented himself to Besuel and Lavan, hoping to convince them not to stand in the way of the match. He therefore added to Avraham’s instructions words that had never been uttered: “my father’s house and my family.” With those words he hoped to convince them that the marriage had been made and ordained in heaven, through Divine providence. (There was nothing deceptive about this. The providence indeed was at work, and the conclusion that the marriage was destined to occur was accurate.) According to the way he told the story to Rivka’s father and brother, Eliezer’s plan to pick the appropriate woman for Yitzchok by posing the camel-watering-at-the-spring challenge was indeed a form of divination. Somehow, his selection of a “sign” from above was answered by G-d. This was certainly going to impress the audience.

Following that script, Eliezer had to make one other small change in relating the story to Besuel and his son. To them he reported (although it was not the way things really happened) that he, Eliezer, did not offer the jewelry to Rivka until after he had inquired of her name. (In fact, Eliezer had been so confident that Hashem would quickly attend to the needs of Eliezer’s great master, that he gave Rivka the bracelets, etc. before ascertaining her name.) After all, Avraham had insisted that the woman come from his own family!

In fact, however, there was no divination. Abraham had not specified that Yitzchok’s wife come from his own immediate family. Eliezer’s test – looking for a young woman with a superlative sense of kindness to others – was a logical, not a supernatural one.

Sefiros Made For Each Other[3]

May I know through her that You have done chesed with my master.

Meshech Chochmah: Read on a kabbalistic level, some details of these pesukim come even more sharply into focus. We understand the Yitzchok’s special characteristic was gevurah, the inwardly-focused capability of living within boundaries and self-discipline, of serving Hashem through exacting, punctilious devotion to His expectations. By wedding that midah to the kindness and chesed of Rivka, the product would be the intermediate position between them: the emes of Yaakov.

Eliezer’s exclamation[4] upon experiencing the superlative chesed of Rivka at the spring becomes that much clearer to us: “Baruch Hashem, G-d of my master Avraham, Who has not withheld His chesed and emes from my master!” He explicitly calls out the midos that, together with Yitzchok’s din, complete a set.

The merging of opposites becomes apparent again towards the end of the parshah, when Rivka encounters Yitzchok for the first time. There, the chesed personality of Rivka meets up with the complete fulfillment of din. Rivka is awe-struck, almost overcome with the presence of her future husband. She has met up with Pachad Yitzchok.

[1] Based on Meshech Chochmah, Bereishis 24:4

[2] Bereishis 24:38

[3] Based on Meshech Chochmah, Bereishis 24:14

[4] Bereishis 24:27