The Torah in telling us that, ‘ In the third month after the Children of Israel …..in that day they came into the wilderness of Sinai, for they journeyed from Rephidim’ (Shmot, 19:1-2), found it necessary to put the coming to Sinai before telling us that they left from Rephidim to go there. It is difficult to grasp the necessity for this longwinded description, yet thee is an important message to be learnt from it.

That generation was a wise one, a ‘dor deah’, so they feared to come to Sinai and the awesome Matan Torah, knowing that they were lacking in the spirituality and the purity to receive the Torah. They lacked the elevation of spirit and mind that would enable them to overcome their weakness.

This problem is discussed in Pirkei Avot (chapter 3,mishnah 1), where the Tannah teaches, ‘reflect on three things and you’ll not come to sin. Know from where you came, unto where you go etc [and in the second part] from a putrid drop, etc’. We should not see the second part of the mishnah as an explanation but rather as a new statement, otherwise he could have taught, ‘know from where you came, from a putrid drop etc’, without the long winded explanation. One should truly separate oneself from the material and elevate ones nefesh if one wishes to keep from sin. However, the Tannah is teaching us that first comes the elevation of the nefesh through the knowledge of the greatness of our source [ the image of G-d], our destination [a world of truth] and that we are privileged to, finally stand before Him. Then when one understands that, then one can reject the evil in the chomer when realizing the source in the putrid drop etc.

Israel did not understand that the nefesh could be elevated first and for that they were punished by the attack of Amalek. They weakened [rafu] their hands in mitzvoth at Rephidim and he cooled them [karecha] on their way. So they where given the days of sefirat haomer within which to elevate the nefesh and then they could come to reject the evil in the chomer.

In this way we can explain the gemara (Berachot, 5a), ‘If a man sees that his yetzer is about to overcome him, he should busy himself with Torah. If that does not help he should read kriat shema and if it persists, he should consider the day of death’. Everybody queries as to why one should not consider the day of death at the outset. That is because that may not be the best way since it may lead him to despair of fighting his yetzer and resign himself to it. So, as says the Tanna in Avot, first one should busy themselves with Torah, that is eternal life and that will breathe in him a new life and elevate his nefesh. Then if he is unsuccessful, he should read kriat shema that will help him drive away the forces of evil through the unity of G-d. If that fails, only then should he consider the day of death, since after he elevated his nefesh somewhat, there is less to fear from despair.

It seems strange that Chazal did not set a ‘mesechtah for Shavuot as they did for all the other chaging; Pesachim for Pesach, Sukah for Sukkot etc. True that there are no mitzvoth on Shavuot except the Shnei Halechem. Nevertheless, it seems that there could be one devoted to this korban, as there is with Yom Kippur which has a mesechta that is devoted to a large degree to the korbanot;

The great Admor Menachem Mendel of Kotsk said that Chazal hid the light of Yom Tovim in mesechtot. We can understand his words from the introduction in the Zohar to the Moadim. There it teaches that G-d hid the great Light that was created on the first day and the reason was so that the evil ones should not benefit from it. This is strange since we know that HaShem is kind and loving to all His creatures. Should we say that out of spite, He withheld the benefit and goodness of His light from the evil ones? Why should it disturb Him that they would also have a benefit from the light; the righteous ones would not suffer thereby? Rather we should say that the Light that was created on the First Day was Chesed and gives to all His Creation the power of love, and since He knew that they would use that Chesed for evil purposes, therefore He hid that great Light from them.

The Chiddushei HaRim of Gur explained this strange introduction of the Zohar to the Moadim, saying that each Chag has a special light and brilliance of its own, all flowing from that Light that was created on the First Day of Creation; There it is written, ‘And He saw the Light and it was good-Tov ‘, from that we get the name Yom Tov. In order that the evil ones should not use these Lights for evil, Chazal hid them in mesechtot- mesechta having the same root as masach, a veil or screen.

The Written Torah was given in public at Sinai and the world heard. When the Tribes crossed the Jordan, they wrote the Torah on great stones, in the 70 languages of Mankind so that all could read it (Sotah, 35b). However the Torah Sheb’al Peh, was given only to Israel, so that the nations of the world have no access to it or part in it. That is why the Torah Sheb’al Peh is hidden in mesechtot. It is not strange therefore, that the special light of each Yom Tov should be enshrined and hidden in a special mesechta..

Shavuot, on which the whole the whole Torah, both the written and the oral, was given in the Ten Commandments, does not need the cover of a mesechta. In the Torah Sheb’al Peh given at Sinai, the nations have no share, as explained above. At Sinai, the Ten Commandments were given in the 70 languages of the world and yet it seems that the other nations heard nothing beyond the sounds of Matan Torah. They came to Bilaam, in fear that these sounds preceded another great flood. They would have had no fear had they heard the actual Torah. So they had no connection to the Torah, neither Written nor Oral given on Shavuot, therefore there is no necessity for the veil or curtain of a mesechta, to hide it from the misuse by evildoers.

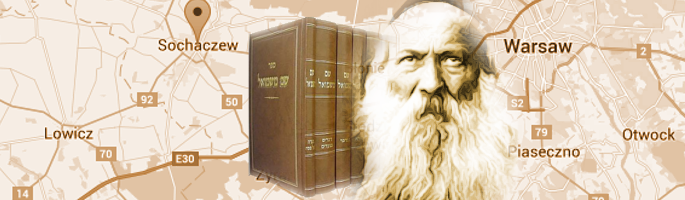

Shem Mi Shmuel, Shavuot 5673 and Yitro 5673.

Text Copyright (c) 2004 by Rabbi Meir Tamari and Torah.org.

D r. Tamari is a renowned economist, Jewish scholar, and founder of the Center For Business Ethics (www.besr.org) in Jerusalem.