Rabbi Shimon said: Be careful with the recitation of the Shema and the prayers. When you pray, do not regard your prayers as a fixed obligation but rather as [the asking for] mercy and supplication before G-d, as the verse states, ‘For gracious and merciful is He, slow to anger, great in kindness, and relenting of the evil decree’ (Joel 2:13). Do not consider yourself wicked in your own eyes.

We are continuing to study the teachings of the five primary students of R. Yochanan ben Zakkai (Mishna 10). This mishna presents the words of R. Shimon, R. Yochanan’s fourth student.

R. Shimon discusses the proper attitude we should have towards prayer. We must on the one hand “be careful” with it. We must view prayer as a duty, one we fulfill on a regular basis — rather than when inspiration comes our way. Yet, continues our mishna, it must not simply become fixed and routine. We must continually turn to G-d asking for His abundant mercy. A day does not go by when we don’t need it.

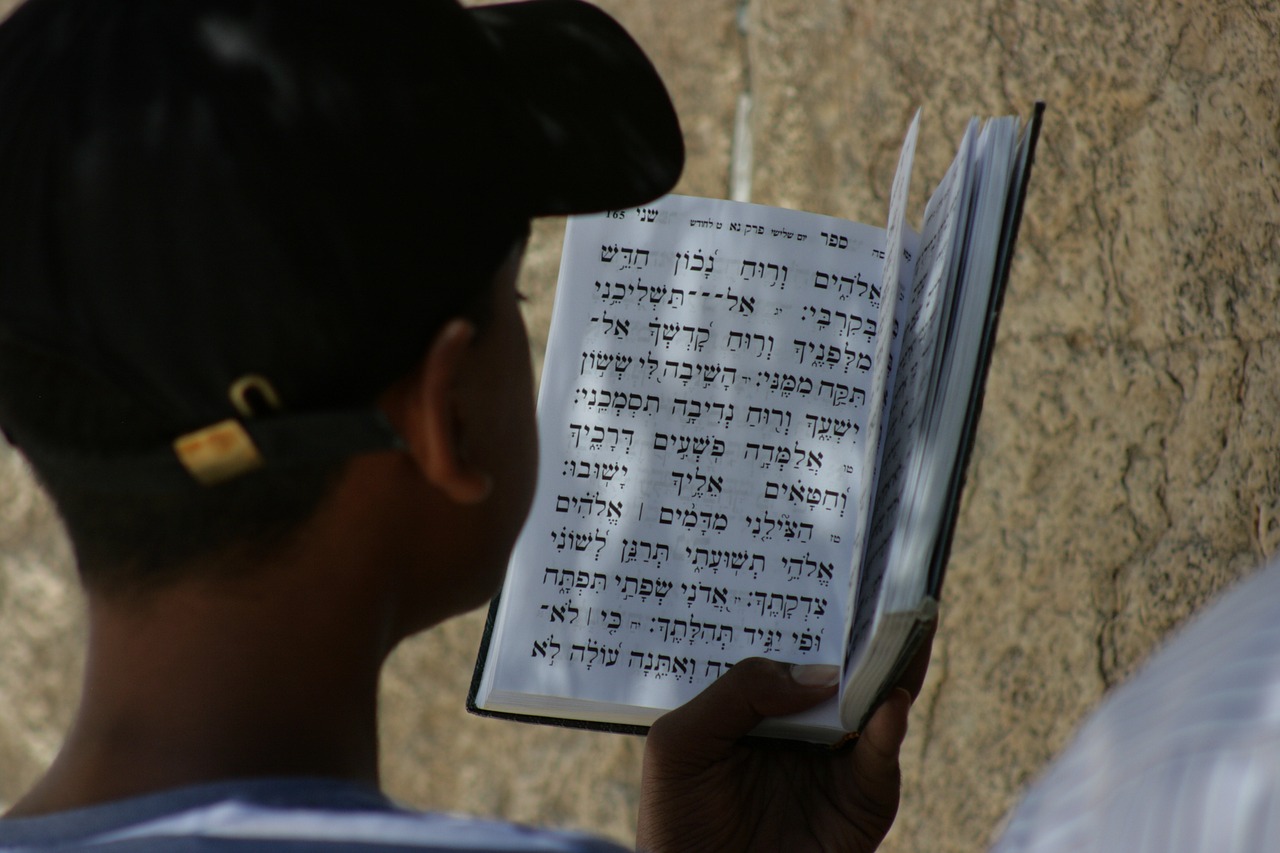

Prayer is set apart from virtually all the other mitzvos (commandments) of the Torah. Every mitzvah is a fulfillment of G-d’s will and brings us closer to Him. But in prayer we communicate directly with G-d. We read in the Shema: “And if you listen to My commandments… to love the L-rd your G-d and to serve Him with all your heart…” (Deuteronomy 11:13). The Talmud explains: What does serving G-d with our hearts refer to? One must say it refers to prayer (Ta’anis 2a). Prayer is inherently a duty of the heart. It is internal. We may articulate the words of our prayers out loud, but it is not the speech with which we serve G-d. It is the thoughts and sincerity behind it.

Prayer further enables us to build a personal relationship with G-d. We talk to our G-d, we confide in Him, we beseech Him, and we express our innermost fears and hopes. And that of course includes confession. He knows, of course, in which ways we’ve sinned to Him. Yet we bring Him into that as well. Sin is not a dirty little part of our lives we attempt to keep away from our G-d, a part of ourselves separate from our religious lives. The same King David who stated, “I have placed the L-rd before me constantly” (Psalms 16:8), proclaimed: “My sin is before me constantly” (51:5). We share our lives with our G-d — both our prides and our misgivings. G-d is our confidante. He is the one we tell our secrets to. For if we can’t share them with G-d, whom truly do we have?

When we open our prayer books and stand before G-d, if we put so much as a moment’s thought into what is happening (we usually don’t), it should be an awe-inspiring experience. The G-d of the heavens and the earth is literally brushing aside the praises of the angels in favor of what Dovid Rosenfeld has to say to Him. We should be terrified, speechless. (At times we are. Some describe the shofar blast as the cry of Israel’s deepest yearnings for G-d — beyond what we are even able to put into words.) The Talmud refers to prayer as “a matter which stands at the height of the universe yet which people do not take seriously” (Brachos 6b).

(I’ve always found it kind of amusing that our brains have sufficient dual-processing capability to read with our lips (and sometimes carry on conversations) while thinking about something utterly different. I guess it’s yet another phenomenon G-d invented to make life challenging.)

After that inspiring introduction, we might almost find our prayer books a letdown. They are long and draining. There are so many rote prayers we must recite — preferably in a language which is at best not our first — that it is difficult enough to take the time to say all the words semi-articulately let alone understand what they all mean and let even more alone be inspired by them. We are obligated to say virtually the exact same prayers day in and out. How does one find inspiration in an activity which allows so little spontaneity and free expression?

The truth is that for much of the earlier part of Jewish history most of the prayers were not in their present standardized form (save the Shema, whose recitation is a Torah obligation). Even the most central part of our prayers, the Shemoneh Esrei, was formulated by the Men of the Great Assembly (see earlier 1:1) during the last few centuries B.C.E. (rather recent by our standards). For that matter, some of the real classics, such as the Passover Haggadah, only reached their present forms far more recently.

The reason for this is because ideally, our prayers should not have to be set out before us. They should be guided by our own inspiration. A person should know him- or herself well enough to know just what his needs are and what he must say to his G-d. The Hebrew word for “pray” — “hitpalail” — is reflexive, meaning literally to reflect oneself. When we pray we turn inwards as much as out. We touch our souls and allow them to touch our G-d. We communicate not only with the G-d outside of ourselves, but equally with that small piece of G-d within.

Thus, originally prayer was as it should be — inspirational, self-motivated, reflecting what each individual knew he or she had to express at that moment. However, as the generations wore on, people became less in touch with themselves and their needs. They lacked the self-awareness to discover G-d wholly on their own. And so, the Sages found it necessary to institutionalize the prayers. We could no longer formulate the prayers ourselves, and so the Sages drew up the outline. Prayer slowly became set and formalized. We were given the perfect — if standardized — formula for what to ask G-d, when to ask, and how.

Thus, in a way we are blessed to have been handed such structure in our prayers. Yet neither should the original intention be missed. Jewish law enjoins us to add our own words in the appropriate places of our prayers (see Shulchan Aruch OC 119:1). We should want to add a little, to speak in our own tongue and include G-d in our daily hopes and fears. There are Chassidim who make it a practice to speak to G-d during the course of their days — at any time and in their own language. (You might remember that from Fiddler on the Roof. I actually found those scenes quite touching.) This might seem intimidating to many of us (myself included) – probably for fear that G-d might actually be listening. In a way it’s comforting to know G-d is there with us — but it many ways, it’s frightening. G-d might be in the synagogue and study hall, but to think that He’s there with us at all times, paying attention to our every word and thought: that is not easy to live with.

But whether or not we wish to be reminded of this reality does not alter the facts. For better or worse G-d is before us. He hears our thoughts and our prayers, and the lines of communication are continuously open. It is we who must be prepared to use them.

Text Copyright © 2008 by Rabbi Dovid Rosenfeld and Torah.org.