It is an eternal decree in your dwelling places for your generations.

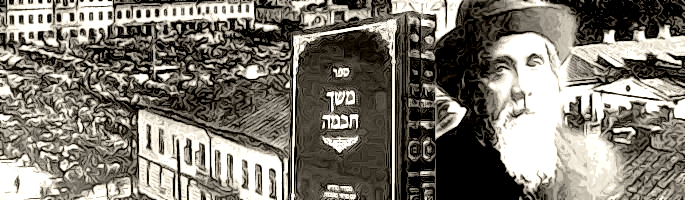

Meshech Chochmah: Mitzvos forge new relationships. Broadly put, some mitzvos bind us to our Creator – tzitzis, tefillin, mezuzah. Others tie us to each other, like gemilas chasodim and the interpersonal commandments. The difference between the two is at work in the separate paths taken by Shabbos on the one hand, and Yom Tov on the other.

Shabbos is more of an individual-friendly institution than a community-builder. Carrying is forbidden, which restricts our ease of sharing with others. So many of the steps of food preparation are forbidden. That removes one of the easiest ways of bringing people together. Instead, Shabbos creates space in which each person can spend quality time studying Torah – or intensifying the relationship between himself and G-d. This does not, however, move people away from each other. To the contrary. As long as Jews are connected to Hashem, they are like radii of a circle, all joined at the origin – their connection to HKBH. Through that common point of connection, they are all bound together, by way of their common relationship with Hashem. But the connection remains indirect, through a third party, rather than directly, one person to the other.

Yom Tov, on the other hand, is one of the mitzvos that binds people directly to each other. It demands that the nation come together in a central place, and there rejoice and help others rejoice. Not only is food preparation permitted, but so are carrying from one domain to another, as well as havara/ burning fuel. Were the two of them forbidden (as they are on Shabbos), it would place a damper on attempts of people to come together.

As the Jews readied themselves to leave Egypt, they were not yet bound to each other in any significant way. They were indeed of one mind and purpose; all were committed to the One G-d of Israel. They were tied together, therefore, only by way of their common link to Hashem. The avodah of that evening, therefore, resembled the conduct of Shabbos. Only those who prepare food before Shabbos have what to eat when it begins. The korban Pesach as well required people to ready themselves before the evening. The korban could be consumed only by those pre-registered for it from the day before.

From that first day, we count seven weeks towards the holiday of Shavuos. The Torah describes the count as “from the morrow of the Shabbos.”[2] It calls the first day of Pesach a “Shabbos” because both bind the people together only through their common devotion to Hashem, without assuming any more direct connection of people with each other. The counting of seven weeks towards the giving of the Torah brings the nation to greater awareness and a loftier spiritual station. Approaching Shavuos, their bond to each other matures, and becomes direct. We should now understand why at precisely this juncture the Torah introduces the laws of the mandatory gifts to the poor[3]– the corners and gleanings of the field to be left to them. The people are now ready for mitzvos that strengthen their relationship with other people, not just with G-d.

This trajectory is unlike that of any other nation. Other people develop a common identity by dint of having lived together on the same land and having evolved a common culture. Klal Yisrael is very different. The glue of its nationhood is the Torah itself. The Jewish people know a strong bond to each other because they have all subordinated themselves to the Torah’s authority. (Heaven itself is subordinate, as it were, to their understanding. The gemara[4] states that it is the human court that determines the calendar – and hence the day a holiday will take place – and not the “objective” reality.)

The implementation of that authority depends on obedience to the Torah greats of each generation. Without that, it is up to each individual’s understanding of the Torah’s demands, and we would be back at the original position of people linked not to each other, but to their loyalty to G-d. Through emunas chachamim and fealty to mesorah, we link ourselves to each other, and function not as individuals, but as a full Torah nation. A common conception of Torah becomes the glue that holds us together, not the evolution of a common culture as is the case with other nations.

When did the interpretive powers of Man first show themselves? The sixth day of Sivan. It was on that day that many expected the giving of the Torah. Moshe, however, reasoned[5] that the “third day” about which Hashem had spoken[6] actually predicted the seventh of Sivan. And that is what happened. The silence at the top of the mountain on the sixth marked, in a sense, the birth of the Jewish people as a Torah nation, bound to each other through a system of human understanding, with gedolei Yisroel and mesorah at the helm. Torah she-b’al-peh had spoken; the people were ready to stay united behind it.

While Chazal differed as to whether Yom Tov requires physical celebration or spiritual focus can substitute for it, there is no disagreement in regard to Shavuos. All authorities require an oneg Yom Tov of physical delights.[7] Shavuos is the time that we became a nation of people bound directly to each other. It should be a time in which people strengthen that bond by sharing the food and friendship at a celebratory table.

This theme is reflected in the special offering of the day as well. The two loaves of bread are not offered on the altar. The kohanim, acting as the agents of the owners, eat the offerings. This stresses the nature of the day, one that is given over to lachem/ “to you,” the people, enjoying not only the Torah, but your coming of age as a nation.