Moshe wrote this Torah and gave it to the Kohanim…

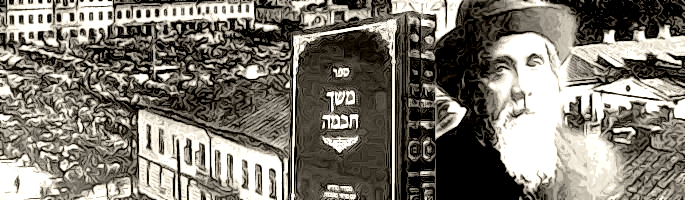

Meshech Chochmah: Moshe didn’t hand over this sefer Torah to the kohanim because he wanted to keep it in the family. He had good reason to. As it turned out, the reason became controversial in the course of time.

The gemara[2] reports that R. Elazar ben Azaryah bore some resemblance to Ezra HaSofer, his illustrious forebear of ten generations earlier. (“His eyes were similar to his [Ezra’s].”) This could simply mean that there was some facial similarity.[3] But there is much more to it than that.

Our pasuk reflects a sobering reality. It makes sense to entrust the continuity of Torah to a relatively small group of people who act as its vigorous protectors and prudent guardians. That was Moshe’s point in handing the Torah – physically – to the kohanim. They would guard it zealously, ensuring that its content would not be violated by the impious or uninformed. At other times, Torah was localized with elders of impeccable background. In the time of the Second Temple, the Perushim kept tight tabs on who should be admitted to the great yeshivos. The working assumption was that if a student wanted Torah badly enough, he would find a way to seek out the great centers of learning – all housed in Yerushalayim.

The very script that was used in Torah scrolls supported this guarded approach to the transmission of Torah. The script was a specialized one. The masses were not familiar with it. It served as a barrier to study, limiting access to Torah study.

Our first record of any change in this approach came from Ezra. He found halachic sanction to change the script to Ashuris, a script brought back from the Babylonian captivity. At the time, it was more “user-friendly.” Ezra was deeply concerned by a confluence of factors that endangered the continuity of Torah. He saw the Jewish community begin to drift off to far-flung locations, all distant from the main centers of Torah learning. He observed vast ignorance concerning fundamentals of Jewish belief and practice, including chilul Shabbos, intermarriage, and the inability of a younger generation to speak Hebrew.[4]

Ezra reasoned that the text of the Torah had to become more accessible to more people. He recognized the risks involved, but was prepared to pay a stiff price for the advantage of making Torah study available to far more people. These risks were in fact realized in the coming centuries of the Second Temple, as students who would have previously been barred from the yeshivos took their places in the great academies. The sub-standard students – as could have been expected – grasped the material imperfectly, and set the stage for the first protracted halachic disputes our people knew. Nonetheless, Ezra felt that the gains outweighed the losses.

The decision was a wise one, according to Chazal[5] who praise Ezra as one through whom it would have been fitting to give the Torah.

Ten generations after Ezra, this issue was still not resolved. Rabban Gamliel, the Nasi, favored a restrictive approach. He was taciturn in his halachic pronouncements: “So I have received from my teachers.”[6] Rather than provide arguments for his position – which would invite all kinds of responses, including wildly invalid ones – he invoked the discipline of mesorah, as if saying, “This is what we have been taught by greater people of previous generations, and nothing more persuasive needs to be said.” Furthermore, he imposed a strict standard for admission to the main academy. Only those whose inner selves matched their outward comportment[7] were accepted.

R. Elazar ben Azaryah believed differently. No sooner had he assumed the position of Nasi than he flung open the doors of the beis medrash, immediately gaining four hundred students who had previously been barred. He leaned towards seeking explanations for what others were content to accept as just-so. Thus, he questions why the Torah would ask people to bring small children to Hakhel when they are too young to understand the message – and he provides an answer.[8] He took pride in the swelling of the ranks of Torah students in his times.

We thus can find a different understanding of the Yerushalmi that speaks of the resemblance of Ezra and R. Elazar ben Azaryh. The “eyes” were similar not in color and shape, but in function. Both possessed eyes that were able to look into the future, and determine a better policy for the continued growth of Torah.